Happy Birthday, Joan Crawford!

“Joan Crawford has passed into myth as a demented martinet whose greatest need or belief concerned padded clothes hangers,” observes author-historian David Thomson in his book The New Biographical Dictionary of Film. You see, a year after Joan’s passing in 1977, her adopted daughter Christina’s controversial child abuse memoir—Mommie Dearest—was published, followed by a big screen adaptation in 1981 (with Faye Dunaway portraying Crawford). Whatever side you’re on in the Joan-vs.-Christina grudge match, however, you can’t deny that the show business career of the woman born Lucille Fay LeSueur in San Antonio, Texas on this date in 1904 has certainly transcended the cartoonish depiction of the Oscar-winning actress in later years. As author Ephraim Katz succinctly sums up in The Film Encyclopedia: “Miss Crawford never ranked among Hollywood’s sex symbols, nor has she been counted among the screen’s accomplished actresses, yet few in filmdom have rivaled her for star glamour and for durability as a top-ranking celluloid queen.”

Joan Crawford’s parents divorced not long after her birth; her mother Anna Bell then married Henry J. Cassin, a vaudeville theatre owner—and Joan went by “Billie Cassin” for a time. Crawford had ambitions of becoming a dancer since her childhood and would later find work as a terpsichorean in nightclubs and traveling revues while working as a shopgirl to earn money for dance lessons. Joan’s later movie persona of the working woman struggling to make good during the Depression was made even more authentic by her real-life employment experiences. Outside of attending St. Agnes Academy and Rockingham Academy in her teen years (both venues as a “working student”) Crawford never progressed beyond primary education.

Joan Crawford’s parents divorced not long after her birth; her mother Anna Bell then married Henry J. Cassin, a vaudeville theatre owner—and Joan went by “Billie Cassin” for a time. Crawford had ambitions of becoming a dancer since her childhood and would later find work as a terpsichorean in nightclubs and traveling revues while working as a shopgirl to earn money for dance lessons. Joan’s later movie persona of the working woman struggling to make good during the Depression was made even more authentic by her real-life employment experiences. Outside of attending St. Agnes Academy and Rockingham Academy in her teen years (both venues as a “working student”) Crawford never progressed beyond primary education.

It was impresario J.J. Schubert who was bowled over by Joan Crawford’s dancing talent; he gave her a part in the chorus line in his 1924 Broadway production of Innocent Eyes. A Hollywood screen test followed not long after for Joan, who was then signed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to a $75-a-week contract. Her feature film debut was as Norma Shearer’s “body double” in Lady of the Night (1925). Crawford would be billed as “Lucille LeSueur” for a few pictures until a studio press agent named Pete Smith (later the star of the “Pete Smith’s Specialties” short subjects) organized a ‘Name the Star” contest in Movie Weekly. “Joan Crawford” was a consolation moniker; the contest winner was actually “Joan Arden” until it was discovered another actress had staked a claim to it.

Beginning with Sally, Irene, and Mary (1925), Joan Crawford began to get noticed in silent feature films. She appeared opposite comedian Harry Langdon in Tramp, Tramp, Tramp (1926); Lon Chaney in The Unknown (1927); and Ramon Novarro in Across to Singapore (1928). Her leading man in Spring Fever (1927), West Point (1928), and The Duke Steps Out (1929) was her good friend William Haines. Joan’s breakout role was in 1928’s Our Dancing Daughters, which allowed her to claim a bit of the “flapper” mystique adopted by the likes of Colleen Moore and Clara Bow. (It also produced follow-ups in Our Modern Maidens [1929] and Our Blushing Brides [1930].)

Beginning with Sally, Irene, and Mary (1925), Joan Crawford began to get noticed in silent feature films. She appeared opposite comedian Harry Langdon in Tramp, Tramp, Tramp (1926); Lon Chaney in The Unknown (1927); and Ramon Novarro in Across to Singapore (1928). Her leading man in Spring Fever (1927), West Point (1928), and The Duke Steps Out (1929) was her good friend William Haines. Joan’s breakout role was in 1928’s Our Dancing Daughters, which allowed her to claim a bit of the “flapper” mystique adopted by the likes of Colleen Moore and Clara Bow. (It also produced follow-ups in Our Modern Maidens [1929] and Our Blushing Brides [1930].)

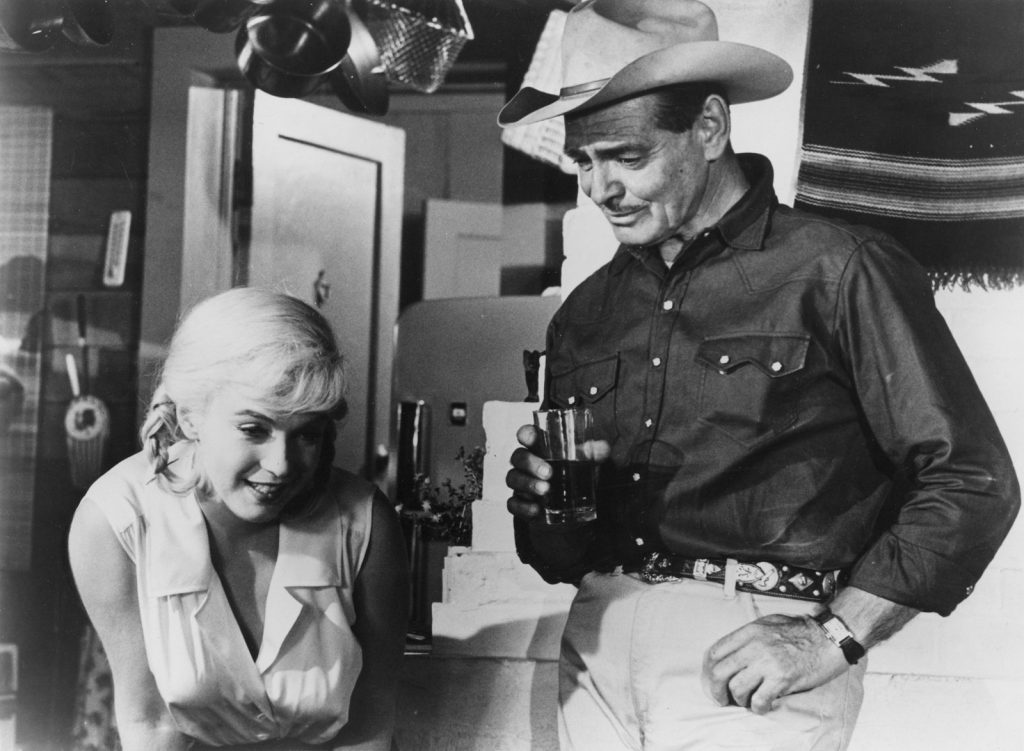

Joan Crawford’s initial foray into talkies was 1929’s Untamed; to rid herself of her Southwestern accent, she took diction and elocution lessons, which paid off handsomely in such films as Dance, Fools, Dance, Laughing Sinners, and Possessed—all three released in 1931 and featuring Clark Gable as her leading man. Crawford and Gable would go on to make five additional pictures during her time at M-G-M including Dancing Lady (1933) and Forsaking All Others (1934). It was Tinsel Town’s worst-kept secret that Joan had a thing for “The King of Hollywood,” yet the two of them never tied the knot. However, she did end up marching down the aisle with three other actors: Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (1929-33), Franchot Tone (1935-39), and Philip Terry (1942-46).

Joan Crawford’s initial foray into talkies was 1929’s Untamed; to rid herself of her Southwestern accent, she took diction and elocution lessons, which paid off handsomely in such films as Dance, Fools, Dance, Laughing Sinners, and Possessed—all three released in 1931 and featuring Clark Gable as her leading man. Crawford and Gable would go on to make five additional pictures during her time at M-G-M including Dancing Lady (1933) and Forsaking All Others (1934). It was Tinsel Town’s worst-kept secret that Joan had a thing for “The King of Hollywood,” yet the two of them never tied the knot. However, she did end up marching down the aisle with three other actors: Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (1929-33), Franchot Tone (1935-39), and Philip Terry (1942-46).

As “Flaemmchen” in the studio’s all-star Grand Hotel (1932), Joan Crawford managed to outshine luminous M-G-M rival Greta Garbo. Though many believe she was miscast as “Sadie Thompson” in Rain (1932), that role led to more mature showcases in vehicles like Sadie McKee (1934) and No More Ladies (1935). The similarity of Joan’s many movie parts would start to hurt her by 1938 when she was pronounced “box office poison.” Although she would stage a “comeback” with one of her finest performances in The Women (1939), her fortunes at M-G-M did not improve and she left the studio in 1943.

As “Flaemmchen” in the studio’s all-star Grand Hotel (1932), Joan Crawford managed to outshine luminous M-G-M rival Greta Garbo. Though many believe she was miscast as “Sadie Thompson” in Rain (1932), that role led to more mature showcases in vehicles like Sadie McKee (1934) and No More Ladies (1935). The similarity of Joan’s many movie parts would start to hurt her by 1938 when she was pronounced “box office poison.” Although she would stage a “comeback” with one of her finest performances in The Women (1939), her fortunes at M-G-M did not improve and she left the studio in 1943.

Joan Crawford found a new home at Warner Bros., but didn’t make a movie there for two years. Her “coming-out party” was a big one, however; as the star of Mildred Pierce (1945), a big screen treatment of the James M. Cain novel, Crawford would be rewarded by her peers with a Best Actress Oscar statuette. Some will argue (myself included) that Joan’s time at the WB produced some of her absolute best vehicles, including Humoresque (1946), Possessed (1947; her second Best Actress Oscar nomination), Daisy Kenyon (1947), Flamingo Road (1949), The Damned Don’t Cry (1950), and This Woman is Dangerous (1952). Although she didn’t make Sudden Fear (1952) at Warner’s (it was an R-K-O release), her performance as a wealthy playwright at the mercy of a homicidal actor (Jack Palance) garnered her a third and final Best Actress Oscar nomination.

Joan Crawford found a new home at Warner Bros., but didn’t make a movie there for two years. Her “coming-out party” was a big one, however; as the star of Mildred Pierce (1945), a big screen treatment of the James M. Cain novel, Crawford would be rewarded by her peers with a Best Actress Oscar statuette. Some will argue (myself included) that Joan’s time at the WB produced some of her absolute best vehicles, including Humoresque (1946), Possessed (1947; her second Best Actress Oscar nomination), Daisy Kenyon (1947), Flamingo Road (1949), The Damned Don’t Cry (1950), and This Woman is Dangerous (1952). Although she didn’t make Sudden Fear (1952) at Warner’s (it was an R-K-O release), her performance as a wealthy playwright at the mercy of a homicidal actor (Jack Palance) garnered her a third and final Best Actress Oscar nomination.

Joan Crawford had something in common with her longtime crush Clark Gable. Like “The King,” Joan experienced white-knuckled terror whenever she had to face a radio microphone in front of a live audience. Actor Sidney Miller recalled in Leonard Maltin’s The Great Radio Broadcast being on a program with Crawford and the actress’ bleeding palms from where her fingernails had dug in clenching her fists so tightly. (“She was so nervous and so scared, I helped her back to the table…she hated radio.”) Still, Joan was a trouper; her radio resume includes appearances on Good News Of 1938/1939, The Gulf Screen Guild Theatre, Hollywood Star Playhouse, The Lux Radio Theatre, Mail Call, Screen Directors’ Playhouse, The Silver Theatre, Stars Over Hollywood, Suspense, and This is Your Life. There’s even a surviving September 8, 1947 audition recording for a proposed series entitled Sound Stage for Joan Crawford, in which Crawford performs with radio veterans like Lurene Tuttle and Gerald Mohr in a half-hour adaptation of Mildred Pierce. (As you may have already guessed, it did not get picked up.)

Joan Crawford had something in common with her longtime crush Clark Gable. Like “The King,” Joan experienced white-knuckled terror whenever she had to face a radio microphone in front of a live audience. Actor Sidney Miller recalled in Leonard Maltin’s The Great Radio Broadcast being on a program with Crawford and the actress’ bleeding palms from where her fingernails had dug in clenching her fists so tightly. (“She was so nervous and so scared, I helped her back to the table…she hated radio.”) Still, Joan was a trouper; her radio resume includes appearances on Good News Of 1938/1939, The Gulf Screen Guild Theatre, Hollywood Star Playhouse, The Lux Radio Theatre, Mail Call, Screen Directors’ Playhouse, The Silver Theatre, Stars Over Hollywood, Suspense, and This is Your Life. There’s even a surviving September 8, 1947 audition recording for a proposed series entitled Sound Stage for Joan Crawford, in which Crawford performs with radio veterans like Lurene Tuttle and Gerald Mohr in a half-hour adaptation of Mildred Pierce. (As you may have already guessed, it did not get picked up.)

By the 1950s, Joan Crawford’s motion picture career had started to fade. She kept her hand in with features like the cult classic Johnny Guitar (1954) and Autumn Leaves (1956), but with the passing of her fourth husband (PepsiCo CEO-Chairman Alfred Steele) in 1959, Joan concentrated on being a “goodwill ambassador” on the company’s behalf. Crawford enjoyed a major box office success with What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962)—co-starring the actress with whom she did not get along, Bette Davis. That camp horror classic paved the way for similar vehicles like Strait-Jacket (1964) and I Saw What You Did (1965). Joan did one or two more features after that (Berserk, Trog), but by that time had started to concentrate on the small screen with appearances on favorites like Route 66 and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (She also made a legendary appearance—though the videotaped record appears lost to history—on the daytime drama The Secret Storm. She played the character that daughter Christina usually essayed but was unable to perform due to illness.) Joan’s last public appearance was in 1974; she retreated into seclusion and passed away in 1977 at the age of 73.

By the 1950s, Joan Crawford’s motion picture career had started to fade. She kept her hand in with features like the cult classic Johnny Guitar (1954) and Autumn Leaves (1956), but with the passing of her fourth husband (PepsiCo CEO-Chairman Alfred Steele) in 1959, Joan concentrated on being a “goodwill ambassador” on the company’s behalf. Crawford enjoyed a major box office success with What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962)—co-starring the actress with whom she did not get along, Bette Davis. That camp horror classic paved the way for similar vehicles like Strait-Jacket (1964) and I Saw What You Did (1965). Joan did one or two more features after that (Berserk, Trog), but by that time had started to concentrate on the small screen with appearances on favorites like Route 66 and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (She also made a legendary appearance—though the videotaped record appears lost to history—on the daytime drama The Secret Storm. She played the character that daughter Christina usually essayed but was unable to perform due to illness.) Joan’s last public appearance was in 1974; she retreated into seclusion and passed away in 1977 at the age of 73.

To celebrate the natal anniversary of the immortal Joan Crawford, we invite you to check out two items in our downloads store. Suspense: Classics features Joanie as the star of a June 2, 1949 broadcast, “The Ten Years,” while Suspense: Tales Well Calculated spotlights her “mike fright” on “Three Lethal Words,” originally broadcast on March 22, 1951. You’ll also find Ms. Crawford among the many stars on the DVD collection Hollywood’s Greatest Screen Legends. Celebrate Joan’s birthday with us but remember…no more wire hangers!

To celebrate the natal anniversary of the immortal Joan Crawford, we invite you to check out two items in our downloads store. Suspense: Classics features Joanie as the star of a June 2, 1949 broadcast, “The Ten Years,” while Suspense: Tales Well Calculated spotlights her “mike fright” on “Three Lethal Words,” originally broadcast on March 22, 1951. You’ll also find Ms. Crawford among the many stars on the DVD collection Hollywood’s Greatest Screen Legends. Celebrate Joan’s birthday with us but remember…no more wire hangers!