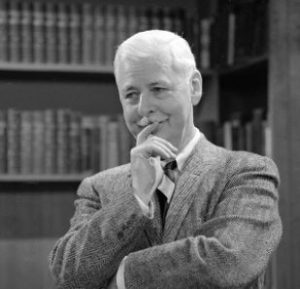

Happy Birthday, Robert Young!

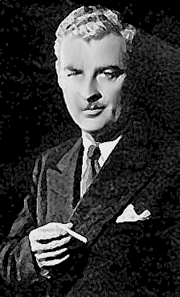

During his lengthy career in show business, Robert George Young—born on this date in 1907—cultivated a characteristic that’s best described in one word: dependable. He was a reliable leading man for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer during the 1930s and early ‘40s, accepting any role that came his way (even if a good many of the films he graced were B-pictures). He would later dominate the small screen with two phenomenally successful television shows; the first a beloved family situation comedy we know as Father Knows Best, and the second an hour-long medical drama in which he played compassionate physician Marcus Welby, M.D. What may not be generally known among the actor’s fans is that he could call himself a veteran of old-time radio as well.

Born in Chicago, IL, Bob left the Windy City as a child when his parents relocated to Seattle, WA…and later to Los Angeles, CA. The acting bug bit Young early, as he performed in numerous dramatic productions during his years of attendance at LA’s Abraham Lincoln High School. Upon graduation, the ambitious thespian studied at night at the Pasadena Playhouse while working various odd jobs during the day (such as bank clerk and loan collector). As he acquired experience on stage, Young made his uncredited movie debut in 1928’s The Campus Vamp. His first onscreen credit was in the Charlie Chan mystery The Black Camel (1931), and upon being summoned to a meeting with MGM mogul Louis B. Mayer, Bob was signed to a contract at the studio known for “more stars than there are in Heaven.”

Born in Chicago, IL, Bob left the Windy City as a child when his parents relocated to Seattle, WA…and later to Los Angeles, CA. The acting bug bit Young early, as he performed in numerous dramatic productions during his years of attendance at LA’s Abraham Lincoln High School. Upon graduation, the ambitious thespian studied at night at the Pasadena Playhouse while working various odd jobs during the day (such as bank clerk and loan collector). As he acquired experience on stage, Young made his uncredited movie debut in 1928’s The Campus Vamp. His first onscreen credit was in the Charlie Chan mystery The Black Camel (1931), and upon being summoned to a meeting with MGM mogul Louis B. Mayer, Bob was signed to a contract at the studio known for “more stars than there are in Heaven.”

Robert Young soon learned as an MGM contract player that when the call came down for him to appear in a movie—any movie—he did so without hesitation. Young revealed in an interview with Leonard Maltin that the studio’s modus operandi as far as a Young picture was concerned simply boiled down to “let’s get Bob.” The actor appeared in a lot of programmers, but he worked hard and many of his early film appearances demonstrate the likability that would cement his cinematic reputation. Among some of his lesser-known films (but interesting all the same) are The Guilty Generation (1931), The Kid from Spain (1932), Men Must Fight (1933), The House of Rothschild (1934), Whom the Gods Destroy (1934) and Secret Agent (1936—directed by Alfred Hitchcock). Young would later observe facetiously that he often got the roles another well-known Robert (Montgomery, that is) turned down…but this allowed him to work alongside such leading ladies as Katharine Hepburn, Margaret Sullavan, Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Helen Hayes and Luise Rainer.

Robert Young soon learned as an MGM contract player that when the call came down for him to appear in a movie—any movie—he did so without hesitation. Young revealed in an interview with Leonard Maltin that the studio’s modus operandi as far as a Young picture was concerned simply boiled down to “let’s get Bob.” The actor appeared in a lot of programmers, but he worked hard and many of his early film appearances demonstrate the likability that would cement his cinematic reputation. Among some of his lesser-known films (but interesting all the same) are The Guilty Generation (1931), The Kid from Spain (1932), Men Must Fight (1933), The House of Rothschild (1934), Whom the Gods Destroy (1934) and Secret Agent (1936—directed by Alfred Hitchcock). Young would later observe facetiously that he often got the roles another well-known Robert (Montgomery, that is) turned down…but this allowed him to work alongside such leading ladies as Katharine Hepburn, Margaret Sullavan, Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Helen Hayes and Luise Rainer.

Every now and then, Young received an opportunity to up his acting game in “A” productions: he landed plum roles in the likes of Three Comrades (1938), Northwest Passage (1940), The Mortal Storm (1940) and Western Union (1941). One of Bob’s finest thespic showcases was in H.M. Pulham, Esq. (1941), in which he plays the title gentleman—an introverted, conservative man who’s coaxed out of his shell by a breathtakingly lovely Hedy Lamarr (it was also one of Lamarr’s best acting turns as well). While he continued to be the model of a good company man, Bob’s employment with MGM was responsible for introducing him to a stint behind the radio microphone as the host of Good News of 1938.

Every now and then, Young received an opportunity to up his acting game in “A” productions: he landed plum roles in the likes of Three Comrades (1938), Northwest Passage (1940), The Mortal Storm (1940) and Western Union (1941). One of Bob’s finest thespic showcases was in H.M. Pulham, Esq. (1941), in which he plays the title gentleman—an introverted, conservative man who’s coaxed out of his shell by a breathtakingly lovely Hedy Lamarr (it was also one of Lamarr’s best acting turns as well). While he continued to be the model of a good company man, Bob’s employment with MGM was responsible for introducing him to a stint behind the radio microphone as the host of Good News of 1938.

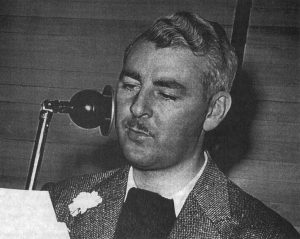

Premiering on November 4, 1937 over NBC, and sponsored by Maxwell House, Good News essentially served as an hour-long promotion for the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio. (It was often joked that it was difficult to tell whether MGM was sponsoring Maxwell House or vice versa). After hosting stints by James Stewart and Robert Taylor, Young got the emcee nod in the fall of 1938. He presided over the festivities for a season before relinquishing the broadcast torch to a rotating series of hosts (included Dick Powell). Such leading celebrity lights as Judy Garland, Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy and Lionel Barrymore were frequent guests…but the Good News series also became famous for featuring the comedy of Frank Morgan and Fanny Brice (as Baby Snooks).

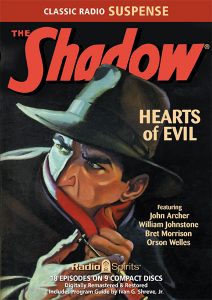

In addition to cavorting with Frank and Fanny, Robert Young was a welcomed guest alongside such radio funsters as Burns & Allen and Fibber McGee & Molly—as well as Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour. Bob was a frequent presence on The Lux Radio Theatre, dramatizing not only his own starring films but those instances where they had to “get Bob,” and he guested on Suspense a number of times as well. Young’s radio resume includes The Cavalcade of America, The CBS Radio Workshop, Command Performance, Family Theatre, Hallmark Playhouse, Hollywood Star Playhouse, Mail Call, The Radio Reader’s Digest, The Screen Guild Theatre, The Silver Theatre, Studio One and Theatre of Romance. In 1943, he starred as a globetrotting newspaperman in a brief Norman Corwin-created series, Passport for Adams. And in the fall of 1944—when Frank Morgan and Fanny Brice went their separate ways in separate shows—Bob returned to Maxwell House as the emcee for what was often referred to as The Frank Morgan Show (which also featured Cass Daley and Eric Blore in the cast).

In addition to cavorting with Frank and Fanny, Robert Young was a welcomed guest alongside such radio funsters as Burns & Allen and Fibber McGee & Molly—as well as Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour. Bob was a frequent presence on The Lux Radio Theatre, dramatizing not only his own starring films but those instances where they had to “get Bob,” and he guested on Suspense a number of times as well. Young’s radio resume includes The Cavalcade of America, The CBS Radio Workshop, Command Performance, Family Theatre, Hallmark Playhouse, Hollywood Star Playhouse, Mail Call, The Radio Reader’s Digest, The Screen Guild Theatre, The Silver Theatre, Studio One and Theatre of Romance. In 1943, he starred as a globetrotting newspaperman in a brief Norman Corwin-created series, Passport for Adams. And in the fall of 1944—when Frank Morgan and Fanny Brice went their separate ways in separate shows—Bob returned to Maxwell House as the emcee for what was often referred to as The Frank Morgan Show (which also featured Cass Daley and Eric Blore in the cast).

No one was more relieved than Bob Young when MGM finally released him from his contract in the early 1940s. Despite his admirable work ethic, the studio often treated him shabbily (L.B. Mayer thought he had “no sex appeal”), and habitually made him wait until the last minute to learn whether or not he’d be with the organization for another year. Young then moved on to 20th Century-Fox, appearing in the likes of Claudia (1943), Claudia and David (1946) and Sitting Pretty (1948). He also did two movies at RKO, both of which are now considered masterpieces of film noir: They Won’t Believe Me and Crossfire (both 1947). On radio, however, his old friend Maxwell House beckoned once again…this time with an offer to play patriarch Jim Anderson in a new NBC radio sitcom: Father Knows Best.

No one was more relieved than Bob Young when MGM finally released him from his contract in the early 1940s. Despite his admirable work ethic, the studio often treated him shabbily (L.B. Mayer thought he had “no sex appeal”), and habitually made him wait until the last minute to learn whether or not he’d be with the organization for another year. Young then moved on to 20th Century-Fox, appearing in the likes of Claudia (1943), Claudia and David (1946) and Sitting Pretty (1948). He also did two movies at RKO, both of which are now considered masterpieces of film noir: They Won’t Believe Me and Crossfire (both 1947). On radio, however, his old friend Maxwell House beckoned once again…this time with an offer to play patriarch Jim Anderson in a new NBC radio sitcom: Father Knows Best.

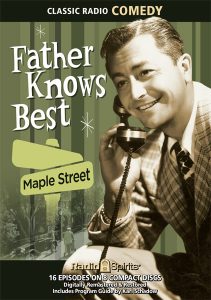

The radio version of Father underwent quite a metamorphosis during its time over the airwaves. In the 1948 audition (which might have been called Father Knows Best?), Young’s character was a knucklehead in the Chester Riley mold. Creator Ed James toned down Jim’s dunderheadedness by the time the show officially went on the air on August 25, 1949, but he was still a far cry from the affable, understanding insurance salesman dad we remember from the small screen. Still, the series was a successful one, lasting until April 25, 1954, and smoothly transitioned to TV in the fall of that same year. It was on the small screen that Father reached its full maturity. The wholesome family sitcom won acting Emmys for Bob and co-star Jane Wyatt during its six-year-run (first a season on CBS, then three years at NBC, then back to CBS for its final two seasons). It was still a Top Ten favorite in its last season: the show only made its final bow in front of the boob tube curtain because its star wanted to pursue other projects.

The radio version of Father underwent quite a metamorphosis during its time over the airwaves. In the 1948 audition (which might have been called Father Knows Best?), Young’s character was a knucklehead in the Chester Riley mold. Creator Ed James toned down Jim’s dunderheadedness by the time the show officially went on the air on August 25, 1949, but he was still a far cry from the affable, understanding insurance salesman dad we remember from the small screen. Still, the series was a successful one, lasting until April 25, 1954, and smoothly transitioned to TV in the fall of that same year. It was on the small screen that Father reached its full maturity. The wholesome family sitcom won acting Emmys for Bob and co-star Jane Wyatt during its six-year-run (first a season on CBS, then three years at NBC, then back to CBS for its final two seasons). It was still a Top Ten favorite in its last season: the show only made its final bow in front of the boob tube curtain because its star wanted to pursue other projects.

And pursue those projects he did: Robert Young followed Father Knows Best with an ambitious comedy-drama that he also created and produced, Window on Main Street. It lasted only a season on CBS, but his third television attempt succeeded beyond his wildest expectations. It began as a 1969 TV-movie entitled A Matter of Humanities, which was so well received that it became a weekly series in September of that same year. On Marcus Welby, M.D., Bob essayed the role of a kindly general practitioner dedicated to his patients. James Brolin co-starred as his partner in practice, and the program ran for seven seasons on ABC from 1969 to 1977. (In the 1970-71 season, it become the first ABC show to finish at #1.) For his efforts, Young would win another acting Emmy. He revisited the role in two “reunion” TV movies in 1984 and 1988…with the last movie featuring his final acting role before his death at the age of 91 in 1998.

And pursue those projects he did: Robert Young followed Father Knows Best with an ambitious comedy-drama that he also created and produced, Window on Main Street. It lasted only a season on CBS, but his third television attempt succeeded beyond his wildest expectations. It began as a 1969 TV-movie entitled A Matter of Humanities, which was so well received that it became a weekly series in September of that same year. On Marcus Welby, M.D., Bob essayed the role of a kindly general practitioner dedicated to his patients. James Brolin co-starred as his partner in practice, and the program ran for seven seasons on ABC from 1969 to 1977. (In the 1970-71 season, it become the first ABC show to finish at #1.) For his efforts, Young would win another acting Emmy. He revisited the role in two “reunion” TV movies in 1984 and 1988…with the last movie featuring his final acting role before his death at the age of 91 in 1998.

Radio Spirits features today’s birthday boy in his signature radio role on Father Knows Best with an 8-CD collection of sixteen sidesplitting broadcasts from 1953—it’s a bit different from the long-running TV version, but that doesn’t make it any less entertaining. You’ll also convulse with laughter at the Andersons’ antics in an additional collection, Maple Street. For dessert, enjoy Robert Young and fellow TV patriarch Danny “Make Room for Daddy” Thomas in an episode of TV’s The Christophers, available on our DVD Stars in Their Shorts. Happy birthday to not only one of our favorite TV dads…but one of our prized television doctors, too!

Radio Spirits features today’s birthday boy in his signature radio role on Father Knows Best with an 8-CD collection of sixteen sidesplitting broadcasts from 1953—it’s a bit different from the long-running TV version, but that doesn’t make it any less entertaining. You’ll also convulse with laughter at the Andersons’ antics in an additional collection, Maple Street. For dessert, enjoy Robert Young and fellow TV patriarch Danny “Make Room for Daddy” Thomas in an episode of TV’s The Christophers, available on our DVD Stars in Their Shorts. Happy birthday to not only one of our favorite TV dads…but one of our prized television doctors, too!