Happy Birthday, Irene Dunne!

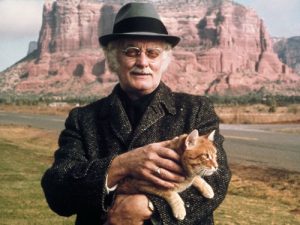

Irene Dunne is acknowledged by many classic movie fans to be the greatest actress who never won an Academy Award. It wasn’t for a lack of trying: she was nominated five times—for Cimarron (1931), Theodora Goes Wild (1936), The Awful Truth (1937—a peerless comic performance), Love Affair (1939), and I Remember Mama (1948)—but putting an Oscar on her fireplace mantle remained an elusive goal. Dunne was never even considered for an honorary trophy! It’s something to consider the next time you get stoked during Oscar season…and it’s as good a way as any to honor the lady born Irene Marie Dunn in Louisville, KY on this date in 1898.

The daughter of Adelaide Henry and Joseph John Dunn, Irene learned to play piano as a young girl (her mother was a concert pianist and music teacher), stoking the fires of ambition to becoming a performer. “Music was as natural as breathing in our house,” Dunne later reflected, and she gained valuable experience by participating in school plays and singing at local churches by the time of her graduation in 1916. Though she earned a college degree to teach art, her musical desires prompted her to enter and win a contest that netted her a scholarship to the prestigious Chicago Musical College. Her dream of becoming an opera singer, however, suffered a setback when her audition with the Metropolitan Opera Company resulted in disappointment.

The daughter of Adelaide Henry and Joseph John Dunn, Irene learned to play piano as a young girl (her mother was a concert pianist and music teacher), stoking the fires of ambition to becoming a performer. “Music was as natural as breathing in our house,” Dunne later reflected, and she gained valuable experience by participating in school plays and singing at local churches by the time of her graduation in 1916. Though she earned a college degree to teach art, her musical desires prompted her to enter and win a contest that netted her a scholarship to the prestigious Chicago Musical College. Her dream of becoming an opera singer, however, suffered a setback when her audition with the Metropolitan Opera Company resulted in disappointment.

Undaunted, Irene Dunne turned to musical theater. Touring cities as the lead in the production Irene (most appropriate), Dunne would make her Broadway debut in 1922 in The Clinging Vine. By 1929, Irene was playing leads in shows like Yours Truly, She’s My Baby, and Luckee Girl…and was touring in the road company version of the successful Jerome Kern-Oscar Hammerstein II production of Show Boat when Hollywood came a-calling. Signed to a contract by RKO, Irene made her film debut in Leathernecking (1930; an adaptation of the stage musical Present Arms), and from that point on graced such features as Cimarron (1931), Symphony of Six Million (1932), Back Street (1932), Thirteen Women (1932), Ann Vickers (1933), The Age of Innocence (1934), Roberta (1935–where she sings the standard Smoke Gets in Your Eyes), and Magnificent Obsession (1935). When RKO remade Show Boat in 1936 (it had been previously filmed in 1929), Irene reprised her original stage role as Magnolia Hawks.

The 1936 film Theodora Goes Wild established Irene Dunne as a fitfully funny movie comedienne, and paved the way for performances in The Awful Truth (1937) and My Favorite Wife (1940), both co-starring Cary Grant. (Dunne and Grant would be teamed for a third film, 1941’s Penny Serenade—a tearjerker leavened with lighter moments.) Charles Boyer was also a frequent co-star; the pair appeared in Love Affair (1939), When Tomorrow Comes (1939), and Together Again (1944). Irene’s film career continued going great guns into the 40s and 50s, with audience favorites like A Guy Named Joe (1943), The White Cliffs of Dover (1944), Anna and the King of Siam (1946), Life with Father (1947), I Remember Mama (1948), and The Mudlark (1950). Her movie swan song was 1952’s It Grows on Trees. She continued to act, but a lack of suitable of scripts redirected her energies towards television, where she was a guest star on the likes of The Ford Television Theatre, The DuPont Show with June Allyson, The General Electric Theater, and Saints and Sinners. Irene never really had a zeal for auditioning like other actresses, once remarking: “I drifted into acting and drifted out. Acting is not everything. Living is.”

The 1936 film Theodora Goes Wild established Irene Dunne as a fitfully funny movie comedienne, and paved the way for performances in The Awful Truth (1937) and My Favorite Wife (1940), both co-starring Cary Grant. (Dunne and Grant would be teamed for a third film, 1941’s Penny Serenade—a tearjerker leavened with lighter moments.) Charles Boyer was also a frequent co-star; the pair appeared in Love Affair (1939), When Tomorrow Comes (1939), and Together Again (1944). Irene’s film career continued going great guns into the 40s and 50s, with audience favorites like A Guy Named Joe (1943), The White Cliffs of Dover (1944), Anna and the King of Siam (1946), Life with Father (1947), I Remember Mama (1948), and The Mudlark (1950). Her movie swan song was 1952’s It Grows on Trees. She continued to act, but a lack of suitable of scripts redirected her energies towards television, where she was a guest star on the likes of The Ford Television Theatre, The DuPont Show with June Allyson, The General Electric Theater, and Saints and Sinners. Irene never really had a zeal for auditioning like other actresses, once remarking: “I drifted into acting and drifted out. Acting is not everything. Living is.”

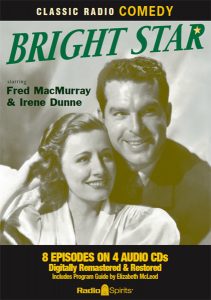

During Radio’s Golden Age, Irene Dunne’s movie star celebrity made her a familiar presence on the medium’s popular anthology programs: The Academy Award Theatre, The Cavalcade of America, Everything for the Boys, Family Theatre, Hallmark Playhouse, The Lux Radio Theatre, Screen Directors’ Playhouse, and The (Gulf/Lady Esther/Camel) Screen Guild Theatre. Dunne also guest starred on such favorites as Command Performance, The Edgar Bergen & Charlie McCarthy Show, and Fibber McGee & Molly. This workout that Irene received in both radio comedy and drama would eventually result in her own starring series: a syndicated 1952-53 program entitled Bright Star, where Dunne portrayed Susan Armstrong, editor of The Hillside Morning Star. Susan had her hands full dealing with the antics of ace reporter George Harvey, portrayed by Fred MacMurray (the two had previously co-starred in Invitation to Happiness [1939] and Never a Dull Moment [1950]). Bright Star also featured the participation of radio pros like Elvia Allman (as Irene’s sardonic domestic), Sheldon Leonard, Betty Lou Gerson, and Harry Von Zell.

During Radio’s Golden Age, Irene Dunne’s movie star celebrity made her a familiar presence on the medium’s popular anthology programs: The Academy Award Theatre, The Cavalcade of America, Everything for the Boys, Family Theatre, Hallmark Playhouse, The Lux Radio Theatre, Screen Directors’ Playhouse, and The (Gulf/Lady Esther/Camel) Screen Guild Theatre. Dunne also guest starred on such favorites as Command Performance, The Edgar Bergen & Charlie McCarthy Show, and Fibber McGee & Molly. This workout that Irene received in both radio comedy and drama would eventually result in her own starring series: a syndicated 1952-53 program entitled Bright Star, where Dunne portrayed Susan Armstrong, editor of The Hillside Morning Star. Susan had her hands full dealing with the antics of ace reporter George Harvey, portrayed by Fred MacMurray (the two had previously co-starred in Invitation to Happiness [1939] and Never a Dull Moment [1950]). Bright Star also featured the participation of radio pros like Elvia Allman (as Irene’s sardonic domestic), Sheldon Leonard, Betty Lou Gerson, and Harry Von Zell.

Irene Dunne left this world for a better one in 1990, and Radio Spirits has a first-rate collection of her signature radio series available in Bright Star, a 4-CD set featuring eight broadcasts from 1953. In addition, there’s a pair of Bright Star episodes on Stop the Press!, our potpourri aggregation of newspaper reporters both homespun and hard-boiled. For visual Dunne, check out one of her finest feature films (delightfully paired with William Powell and featuring a young Elizabeth Taylor) in Life with Father, the movie adaptation of the long-running Broadway family comedy. Finally, Irene is represented on our DVD Stars in Their Shorts with a 1950 star-studded short entitled You Can Change the World. Happy birthday to the amazing Irene Dunne!

Irene Dunne left this world for a better one in 1990, and Radio Spirits has a first-rate collection of her signature radio series available in Bright Star, a 4-CD set featuring eight broadcasts from 1953. In addition, there’s a pair of Bright Star episodes on Stop the Press!, our potpourri aggregation of newspaper reporters both homespun and hard-boiled. For visual Dunne, check out one of her finest feature films (delightfully paired with William Powell and featuring a young Elizabeth Taylor) in Life with Father, the movie adaptation of the long-running Broadway family comedy. Finally, Irene is represented on our DVD Stars in Their Shorts with a 1950 star-studded short entitled You Can Change the World. Happy birthday to the amazing Irene Dunne!