“Friendship, friendship…just a perfect blendship…”

The Golden Age of Radio was always welcoming to dizzy women who marched to the beat of a different drummer—Gracie Allen (with her “illogical logic”) and Jane Ace being two primary examples. But both Gracie and Jane had stiff competition in the form of the medium’s favorite “dumb blonde,” Irma Peterson, the lovably dumb stenographer on the sitcom My Friend Irma. According to historian John Dunning in On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio, Irma “had neither the malapropian qualities of Ace nor the dubiously screwy logic of Allen.” She just wasn’t too terribly bright. For example, when her roommate Jane Stacy once suggested replacing the apartment’s wall brackets with a bridge lamp for better lighting, Irma responded: “But, Jane—what if we want to play gin rummy?” The program that became one of radio’s bright lights of comedy premiered over CBS on this date in 1947.

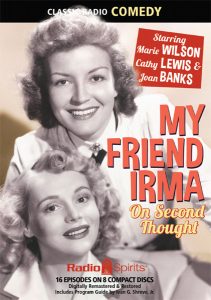

The central premise of My Friend Irma—two career girls, sharing an apartment and struggling to survive in New York City—was certainly not a new one. (One strong film example is 1942’s My Sister Eileen). But writer Cy Howard, who gave up a career in sales to become a professional writer, put a new twist on the concept by making the titular character of My Friend Irma the stereotypical dumb blonde to end all dumb blondes. Howard had spotted actress Marie Wilson performing in the stage revue Ken Murray’s Blackouts and convinced her to take a chance and star in the radio comedy. Casting Cathy Lewis, a radio veteran, as Irma’s levelheaded roomie Jane was also a masterstroke. Lewis purportedly got the gig due to her impatience at the audition (she was running late for another one) and Howard loved the irritation expressed in her voice.

The central premise of My Friend Irma—two career girls, sharing an apartment and struggling to survive in New York City—was certainly not a new one. (One strong film example is 1942’s My Sister Eileen). But writer Cy Howard, who gave up a career in sales to become a professional writer, put a new twist on the concept by making the titular character of My Friend Irma the stereotypical dumb blonde to end all dumb blondes. Howard had spotted actress Marie Wilson performing in the stage revue Ken Murray’s Blackouts and convinced her to take a chance and star in the radio comedy. Casting Cathy Lewis, a radio veteran, as Irma’s levelheaded roomie Jane was also a masterstroke. Lewis purportedly got the gig due to her impatience at the audition (she was running late for another one) and Howard loved the irritation expressed in her voice.

“Now, don’t get me wrong,” Jane might muse at the start of a broadcast. “I love that girl—most people do. It’s just that Mother Nature gave some girls brains, intelligence, and cleverness…but with Irma…well, Mother Nature slipped her a mickey.” Despite her frequent putdowns of her roommate, Jane and Irma were almost like sisters…and fiercely protective of one another. (Jane affectionately called Irma “Cookie.”) They resided in a dilapidated rooming house (8224 West 73rd Street, NYC) run by Kathleen O’Reilly (first played by Jane Morgan, then Gloria Gordon). This feisty Irish lass was constantly engaged in a war of words with the girls’ upstairs neighbor, violinist Professor Kropotkin (Hans Conried). Kropotkin’s entrance on the show each week was signaled by a soft knock on the girls’ apartment door and a meek “It’s only me…Professor Kropotkin.” Kropotkin would also toss a bit of flattery toward his downstairs neighbors: “Hello, Janie and Irma—my two little jigsaw puzzles…one complete, and one a few pieces are missing.”

“Now, don’t get me wrong,” Jane might muse at the start of a broadcast. “I love that girl—most people do. It’s just that Mother Nature gave some girls brains, intelligence, and cleverness…but with Irma…well, Mother Nature slipped her a mickey.” Despite her frequent putdowns of her roommate, Jane and Irma were almost like sisters…and fiercely protective of one another. (Jane affectionately called Irma “Cookie.”) They resided in a dilapidated rooming house (8224 West 73rd Street, NYC) run by Kathleen O’Reilly (first played by Jane Morgan, then Gloria Gordon). This feisty Irish lass was constantly engaged in a war of words with the girls’ upstairs neighbor, violinist Professor Kropotkin (Hans Conried). Kropotkin’s entrance on the show each week was signaled by a soft knock on the girls’ apartment door and a meek “It’s only me…Professor Kropotkin.” Kropotkin would also toss a bit of flattery toward his downstairs neighbors: “Hello, Janie and Irma—my two little jigsaw puzzles…one complete, and one a few pieces are missing.”

Both Jane and Irma worked as secretaries—Irma’s employer was attorney Milton J. Clyde (Alan Reed). The lawyer was constantly exasperated by his hare-brained assistant, but reluctant to fire her because he knew no one else would be able to decipher Irma’s screwy filing system. Jane not only worked for wealthy Richard Rhinelander III (Leif Erickson), she had a big crush on her boss, and was unabashedly determined to become “Mrs. Richard Rhinelander III.” (“What good will that do if he has two other wives?” Irma once mused.) Irma’s love interest would never appear in the social register like her best friend’s boss. Al (who had no last name) was one of radio’s most memorable loafers—a man permanently on the dole and completely unembarrassed by it. Wonderfully portrayed by John Brown, Al was short on ambition but long on inspiration—always cooking up a Ralph Kramden-like scheme that was guaranteed to put him in the chips. Whenever he found himself in a jam (a weekly occurrence), audiences waited for Al to get on the phone with the only man who could give him the right advice: “Hello, Joe? Al. Got a problem…”

Both Jane and Irma worked as secretaries—Irma’s employer was attorney Milton J. Clyde (Alan Reed). The lawyer was constantly exasperated by his hare-brained assistant, but reluctant to fire her because he knew no one else would be able to decipher Irma’s screwy filing system. Jane not only worked for wealthy Richard Rhinelander III (Leif Erickson), she had a big crush on her boss, and was unabashedly determined to become “Mrs. Richard Rhinelander III.” (“What good will that do if he has two other wives?” Irma once mused.) Irma’s love interest would never appear in the social register like her best friend’s boss. Al (who had no last name) was one of radio’s most memorable loafers—a man permanently on the dole and completely unembarrassed by it. Wonderfully portrayed by John Brown, Al was short on ambition but long on inspiration—always cooking up a Ralph Kramden-like scheme that was guaranteed to put him in the chips. Whenever he found himself in a jam (a weekly occurrence), audiences waited for Al to get on the phone with the only man who could give him the right advice: “Hello, Joe? Al. Got a problem…”

Other characters on My Friend Irma included Mrs. Rhinelander (Myra Marsh), who wasn’t completely sold on Jane’s intentions to march her son up the matrimonial aisle. And there was Amber Lipscott, a friend of Irma’s who had a hilarious Noo Yawk accent (voiced by the one-and-only Bea Benaderet). Later in the show’s radio/TV run, Cathy Lewis left the show and Irma got a new roommate in Kay Foster, played by Mary Shipp. Shipp had been a regular (as Miss Spaulding) on Cy Howard’s other successful radio creation, Life with Luigi, which also featured Alan Reed (as Pasquale) and Hans Conried (Schultz). For a brief period in 1949, Lewis had been replaced in the role of Jane by actress Joan Banks (while Cathy recuperated from an illness).

Other characters on My Friend Irma included Mrs. Rhinelander (Myra Marsh), who wasn’t completely sold on Jane’s intentions to march her son up the matrimonial aisle. And there was Amber Lipscott, a friend of Irma’s who had a hilarious Noo Yawk accent (voiced by the one-and-only Bea Benaderet). Later in the show’s radio/TV run, Cathy Lewis left the show and Irma got a new roommate in Kay Foster, played by Mary Shipp. Shipp had been a regular (as Miss Spaulding) on Cy Howard’s other successful radio creation, Life with Luigi, which also featured Alan Reed (as Pasquale) and Hans Conried (Schultz). For a brief period in 1949, Lewis had been replaced in the role of Jane by actress Joan Banks (while Cathy recuperated from an illness).

My Friend Irma was a huge hit for the Columbia Broadcasting System, likely due to its plum time slot (it aired after The Lux Radio Theatre, one of radio’s most popular shows). After being sustained in early broadcasts, it quickly secured a sponsor in Lever Brothers (for Swan Soap) and later in its run, the Pearson Pharmacal Company (Ennds breath mints/Eye-Gene eye drops) and R.J. Reynolds Tobacco (Camel/Cavalier cigarettes) paid the bills. The success of the show led to two theatrical films based on the program, My Friend Irma (1949) and My Friend Irma Goes West (1950). Both movies remain quite popular today, no doubt due to the participation of an up-and-coming comedy duo, Dean Martin & Jerry Lewis.

My Friend Irma was a huge hit for the Columbia Broadcasting System, likely due to its plum time slot (it aired after The Lux Radio Theatre, one of radio’s most popular shows). After being sustained in early broadcasts, it quickly secured a sponsor in Lever Brothers (for Swan Soap) and later in its run, the Pearson Pharmacal Company (Ennds breath mints/Eye-Gene eye drops) and R.J. Reynolds Tobacco (Camel/Cavalier cigarettes) paid the bills. The success of the show led to two theatrical films based on the program, My Friend Irma (1949) and My Friend Irma Goes West (1950). Both movies remain quite popular today, no doubt due to the participation of an up-and-coming comedy duo, Dean Martin & Jerry Lewis.

My Friend Irma would also make a transition to the small screen, premiering on CBS-TV on January 8, 1952. Its television run was a brief one—though creator Cy Howard had proposed a spin-off, My Wife Irma, to the network that would find Irma now married to a Park Avenue millionaire (I thought that was Jane’s racket?). Steve Dunne was purportedly considered for the role of Irma’s hubby, but the series never materialized. My Friend Irma fans had to soldier on after the radio series’ departure on August 24, 1954 with a series of comic books (that began in 1950) featuring the confused heroine, published by Atlas (later Marvel) and written by future Marvel Comics figurehead Stan Lee (and illustrated by Dan DeCarlo!) until 1955.

My Friend Irma would also make a transition to the small screen, premiering on CBS-TV on January 8, 1952. Its television run was a brief one—though creator Cy Howard had proposed a spin-off, My Wife Irma, to the network that would find Irma now married to a Park Avenue millionaire (I thought that was Jane’s racket?). Steve Dunne was purportedly considered for the role of Irma’s hubby, but the series never materialized. My Friend Irma fans had to soldier on after the radio series’ departure on August 24, 1954 with a series of comic books (that began in 1950) featuring the confused heroine, published by Atlas (later Marvel) and written by future Marvel Comics figurehead Stan Lee (and illustrated by Dan DeCarlo!) until 1955.

My Friend Irma is one of several radio classics featured in our potpourri collection Great Radio Sitcoms. It’s guaranteed to whet your appetite for full-blown Irma in the set On Second Thought (which features a program guide booklet penned by yours truly!). Finally, if you’re interested in learning more about the talented lady who made us laugh as the daffy Irma, we’d like to recommend my friend Charles Transberg’s book Not So Dumb: The Life and Career of Marie Wilson. Happy anniversary, Irma and Jane!