“Two people who live together…and like it!”

Old-time radio author-historian Jim Cox describes My Favorite Husband as “a dress rehearsal for the main event” in his indispensable reference book The Great Radio Sitcoms. “My Favorite Husband was like a pilot for a television series that has never ceased,” he writes. “While the final production was better than its forerunner, every sitcom requires a rehearsal.” The “final production” Cox alludes to is I Love Lucy, one of the most popular situation comedies in the history of the broadcast medium. Husband, which premiered over CBS on this date in 1948, was the blueprint for Lucy. Many of Lucy’s classic episodes were recycled from earlier Husband scripts, and elements of the radio show would work their way into Lucille Ball’s later television efforts as well.

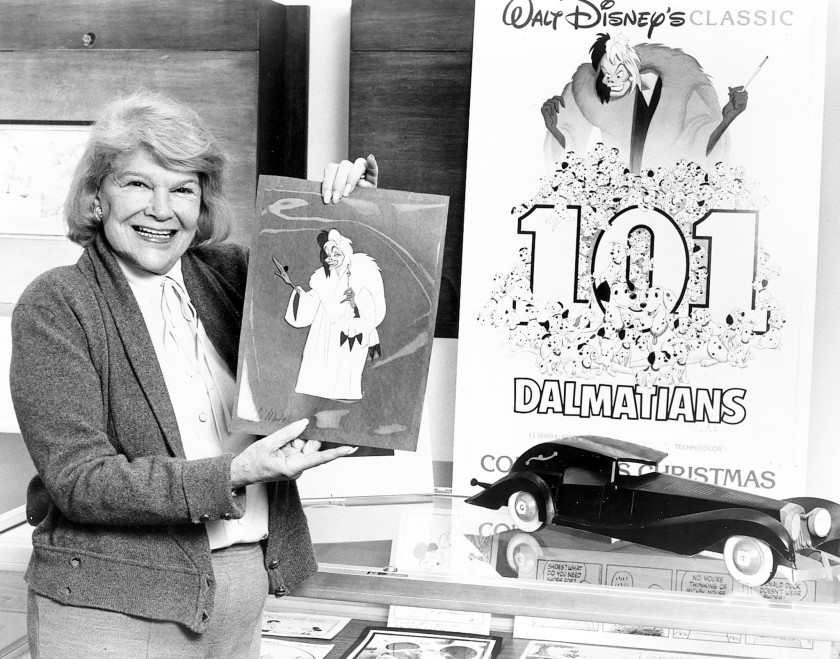

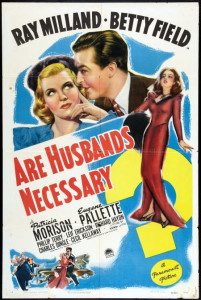

My Favorite Husband’s origins can be traced to a 1941 novel penned by Isabel Scott Rorick: Mr. & Mrs. Cugat: The Record of a Happy Marriage. Rorick’s book had already been adapted for the silver screen as a 1942 Ray Milland-Betty Field comedy, Are Husbands Necessary? However, as Lucy reminisced in her autobiography Love, Lucy, it was CBS vice president Hubbell Robinson who approached her in 1946 with the idea of doing a radio version. Anxious to repair her then dicey marriage with bandleader Desi Arnaz—who had justly acquired a reputation as being a wandering husband whenever he was on the road—Lucy was amenable to the idea. Of course, she wanted Desi to play her spouse on the program. The CBS brass balked at this, arguing that no one would believe Arnaz was her husband, despite the fact that…well, that he was her husband. “I think it helps make a domestic comedy more believable when the audience knows the couple are actually married,” she explained to The Powers That Be. (Ball had also observed that radio, as a medium, was kinder to the married home life of entertainers, as witnessed in such couples as Jack Benny & Mary Livingstone and George Burns & Gracie Allen.)

My Favorite Husband’s origins can be traced to a 1941 novel penned by Isabel Scott Rorick: Mr. & Mrs. Cugat: The Record of a Happy Marriage. Rorick’s book had already been adapted for the silver screen as a 1942 Ray Milland-Betty Field comedy, Are Husbands Necessary? However, as Lucy reminisced in her autobiography Love, Lucy, it was CBS vice president Hubbell Robinson who approached her in 1946 with the idea of doing a radio version. Anxious to repair her then dicey marriage with bandleader Desi Arnaz—who had justly acquired a reputation as being a wandering husband whenever he was on the road—Lucy was amenable to the idea. Of course, she wanted Desi to play her spouse on the program. The CBS brass balked at this, arguing that no one would believe Arnaz was her husband, despite the fact that…well, that he was her husband. “I think it helps make a domestic comedy more believable when the audience knows the couple are actually married,” she explained to The Powers That Be. (Ball had also observed that radio, as a medium, was kinder to the married home life of entertainers, as witnessed in such couples as Jack Benny & Mary Livingstone and George Burns & Gracie Allen.)

CBS refused to budge, so Mrs. Arnaz relented and My Favorite Husband debuted as a “special preview program” on July 5, 1948. Lucy starred as socialite-turned-housewife Elizabeth (Liz) Elliott Cugat, and Lee Bowman played her husband George, former playboy-turned-bank-vice-president. The reception to the show was quite positive, and CBS gave the greenlight for Husband to continue for the remainder of the summer. Bowman, however, was forced to bow out due to previous commitments and he handed off his role to actor Richard Denning, who would play George Cugat until the show left the radio airwaves. Bowman wasn’t the only individual whose stint with Husband would be a short one. The series was being written by Frank Fox and Bill Davenport, but only until their regular writing jobs returned in the fall with The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet (they were “on loan,” to speak). CBS vice president Harry Ackerman assigned the scripting of Husband to a pair of network staffers, Madelyn Pugh and Bob Carroll, Jr.

CBS refused to budge, so Mrs. Arnaz relented and My Favorite Husband debuted as a “special preview program” on July 5, 1948. Lucy starred as socialite-turned-housewife Elizabeth (Liz) Elliott Cugat, and Lee Bowman played her husband George, former playboy-turned-bank-vice-president. The reception to the show was quite positive, and CBS gave the greenlight for Husband to continue for the remainder of the summer. Bowman, however, was forced to bow out due to previous commitments and he handed off his role to actor Richard Denning, who would play George Cugat until the show left the radio airwaves. Bowman wasn’t the only individual whose stint with Husband would be a short one. The series was being written by Frank Fox and Bill Davenport, but only until their regular writing jobs returned in the fall with The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet (they were “on loan,” to speak). CBS vice president Harry Ackerman assigned the scripting of Husband to a pair of network staffers, Madelyn Pugh and Bob Carroll, Jr.

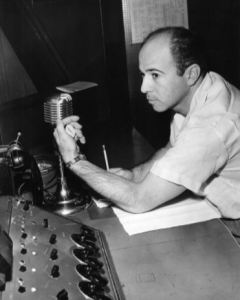

Ackerman would also hire an individual who, as head writer, would make important changes to My Favorite Husband. Writer Jess Oppenheimer had made his name at the network working for stars like Fanny Brice. In fact, it was after being dismissed from Brice’s The Baby Snooks Show (CBS gave the star her pink slip at the end of the 1947-48 season) that Jess was encouraged by Ackerman to submit a script to Husband…with Ackerman being so bowled over he offered the head writer’s job to Oppenheimer. Jess was hesitant to take the gig—he had heard that Lucy had a reputation as a “strong personality”—but eventually agreed to accept the position. To Oppenheimer’s surprise, Ackerman informed him that not only would he be the head writer but the director-producer as well.

Ackerman would also hire an individual who, as head writer, would make important changes to My Favorite Husband. Writer Jess Oppenheimer had made his name at the network working for stars like Fanny Brice. In fact, it was after being dismissed from Brice’s The Baby Snooks Show (CBS gave the star her pink slip at the end of the 1947-48 season) that Jess was encouraged by Ackerman to submit a script to Husband…with Ackerman being so bowled over he offered the head writer’s job to Oppenheimer. Jess was hesitant to take the gig—he had heard that Lucy had a reputation as a “strong personality”—but eventually agreed to accept the position. To Oppenheimer’s surprise, Ackerman informed him that not only would he be the head writer but the director-producer as well.

Getting acclimated to the working conditions on My Favorite Husband was not an easy task for Jess Oppenheimer, but he was soon tinkering with the formula to make the show funnier. When Husband first went on the air, the characters of Liz and George Cugat were quite upwardly mobile, owing to George’s status as bank vice president. Oppenheimer made them a little more middle class, hinting that George’s title was more window dressing than anything truly financially substantial. Jess also toned-down Liz’s sophistication—using Fanny Brice’s Baby Snooks as a template, he made Liz more childlike and impulsive. The final touch was changing the couple’s last name to “Cooper.” (Bandleader Xavier Cugat and his wife had threatened the show with a lawsuit over use of their name.)

Getting acclimated to the working conditions on My Favorite Husband was not an easy task for Jess Oppenheimer, but he was soon tinkering with the formula to make the show funnier. When Husband first went on the air, the characters of Liz and George Cugat were quite upwardly mobile, owing to George’s status as bank vice president. Oppenheimer made them a little more middle class, hinting that George’s title was more window dressing than anything truly financially substantial. Jess also toned-down Liz’s sophistication—using Fanny Brice’s Baby Snooks as a template, he made Liz more childlike and impulsive. The final touch was changing the couple’s last name to “Cooper.” (Bandleader Xavier Cugat and his wife had threatened the show with a lawsuit over use of their name.)

Oppenheimer also had the brainstorm to ask Lucy to attend a Jack Benny Show broadcast and watch how effective Jack was at milking laughs from an audience. Realizing that she could make the show funnier by interacting with the crowd rather than just reading lines from a script, Lucy adopted this new policy with gusto. (“[T]here were times I thought we’d have to catch her with a butterfly net to get her back to the microphone,” Oppenheimer recalled in his son Gregg’s Laughs, Luck…and Lucy: How I Came to Create the Most Popular Sitcom of All Time.) He wasn’t quite as fortunate with Lucy’s co-star, however; Denning told him: “If I take my eyes or finger off that script, I’ll never find my place again.”

Jess Oppenheimer continued to make successful alterations to My Favorite Husband. Realizing that the Coopers could use the comic contrast of an older couple (the wife of which could act as Liz’s confidant), the writers started to beef up the role of Rudolph Atterbury, George’s boss at the bank…and assigned the role to radio’s indispensable Gale Gordon. (Atterbury had previously been played on Husband by the likes of Hans Conried and Joseph Kearns.) Bea Benaderet played Iris Atterbury, always willing to help Liz carry out some zany scheme. Benaderet was no stranger to Husband, having previously emoted as George’s mother Leticia (a role that then went to Eleanor Audley. The supporting cast of Husband included Ruth Perrott (as dutiful maid Katie), Richard Crenna, John Hiestand, Hal March, Frank Nelson, Doris Singleton, and many more.

Jess Oppenheimer continued to make successful alterations to My Favorite Husband. Realizing that the Coopers could use the comic contrast of an older couple (the wife of which could act as Liz’s confidant), the writers started to beef up the role of Rudolph Atterbury, George’s boss at the bank…and assigned the role to radio’s indispensable Gale Gordon. (Atterbury had previously been played on Husband by the likes of Hans Conried and Joseph Kearns.) Bea Benaderet played Iris Atterbury, always willing to help Liz carry out some zany scheme. Benaderet was no stranger to Husband, having previously emoted as George’s mother Leticia (a role that then went to Eleanor Audley. The supporting cast of Husband included Ruth Perrott (as dutiful maid Katie), Richard Crenna, John Hiestand, Hal March, Frank Nelson, Doris Singleton, and many more.

My Favorite Husband started out as a sustained series for CBS Radio, but it eventually found a sponsor in General Mills, allowing Lucille Ball to greet the studio and listening audiences each week with an enthusiastic “Jell-O, everybody!” The program also became famous for its memorable closing commercials featuring Lucy and announcer Bob Lemond, with Lucy playing famous Mother Goose/storybook characters like Goldilocks and Little Miss Muffet. My Favorite Husband was a success for The Tiffany Network until its curtain closing on March 31, 1951. A TV version of Husband later aired over CBS from 1953 to 1955, with Joan Caulfield and Barry Nelson in the Ball-Denning roles. Meanwhile, Lucy would get the opportunity to play housewife to her real-life husband…but that’s a post for another day.

My Favorite Husband started out as a sustained series for CBS Radio, but it eventually found a sponsor in General Mills, allowing Lucille Ball to greet the studio and listening audiences each week with an enthusiastic “Jell-O, everybody!” The program also became famous for its memorable closing commercials featuring Lucy and announcer Bob Lemond, with Lucy playing famous Mother Goose/storybook characters like Goldilocks and Little Miss Muffet. My Favorite Husband was a success for The Tiffany Network until its curtain closing on March 31, 1951. A TV version of Husband later aired over CBS from 1953 to 1955, with Joan Caulfield and Barry Nelson in the Ball-Denning roles. Meanwhile, Lucy would get the opportunity to play housewife to her real-life husband…but that’s a post for another day.

Radio Spirits’ brand-new potpourri collection of radio comedy programs, Great Radio Sitcoms, features a May 21, 1950 broadcast of My Favorite Husband that is guaranteed to brighten your spirits on this anniversary of one of radio’s most entertaining programs!