Happy Birthday, Judy Canova!

At the height of her popularity in the 1940s, Judy Canova—born in Starke, Florida on this date in 1913—started a pigtails-and-calico fad among female students on college campuses. Juliette Canova, whose mother Henrietta Perry was also a singer, had serious aspirations in the field of music…and in my opinion, had the pipes to pull it off. However, because her early vaudeville career consisted of singing and yodeling with her siblings Annie and Zeke (as The Three Canovas)—not to mention her brief marriage to Bob Burns (a.k.a. “The Arkansas Traveler”) in the 1930s—Judy was destined instead to become America’s favorite female hillbilly in radio, movies and TV.

Judy, Annie and Zeke got their start in various nightclubs in the Florida area before hitting the big time at The Village Barn in Manhattan. Their efforts soon landed them a spot in the Broadway stage revue Calling All Stars, and the Canovas attracted the attention of Rudy Vallee, who arranged for them to appear on his Fleischmann Hour in 1933. The three siblings then moved from The Vagabond Lover to The King of Jazz—none other than Paul Whiteman, whose Musical Varieties program welcomed them from 1936-37. The Canovas also made regular appearances in the fall of 1938 on The Chase & Sanborn Hour, the popular Sunday night variety hour that launched ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and dummy Charlie McCarthy to prominence.

Judy, Annie and Zeke got their start in various nightclubs in the Florida area before hitting the big time at The Village Barn in Manhattan. Their efforts soon landed them a spot in the Broadway stage revue Calling All Stars, and the Canovas attracted the attention of Rudy Vallee, who arranged for them to appear on his Fleischmann Hour in 1933. The three siblings then moved from The Vagabond Lover to The King of Jazz—none other than Paul Whiteman, whose Musical Varieties program welcomed them from 1936-37. The Canovas also made regular appearances in the fall of 1938 on The Chase & Sanborn Hour, the popular Sunday night variety hour that launched ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and dummy Charlie McCarthy to prominence.

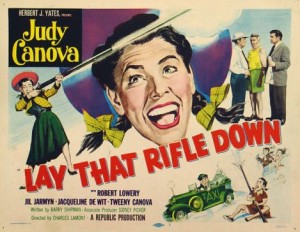

In addition to their radio work, the Canova siblings began appearing together in feature films—they’re among the specialty acts in the 1935 Warner Bros. picture In Caliente, and they also turned up in a number of Paramount movies like Artists and Models (1937) and Thrill of a Lifetime (1937). When Judy went out on her own as a solo act, she signed a contract with Republic Pictures. For many years, she would be that studio’s bread-and-butter with box office attractions like Scatterbrain (1940), Sis Hopkins (1941) and Joan of Ozark (1942). (Her last film for Republic was 1955’s Lay That Rifle Down, ending a most fruitful fifteen-year partnership with the studio best known for B-Westerns and serials,)

In addition to their radio work, the Canova siblings began appearing together in feature films—they’re among the specialty acts in the 1935 Warner Bros. picture In Caliente, and they also turned up in a number of Paramount movies like Artists and Models (1937) and Thrill of a Lifetime (1937). When Judy went out on her own as a solo act, she signed a contract with Republic Pictures. For many years, she would be that studio’s bread-and-butter with box office attractions like Scatterbrain (1940), Sis Hopkins (1941) and Joan of Ozark (1942). (Her last film for Republic was 1955’s Lay That Rifle Down, ending a most fruitful fifteen-year partnership with the studio best known for B-Westerns and serials,)

In the fall of 1943, Judy launched her most successful radio venture with the appropriately titled The Judy Canova Show (though it was briefly known as Rancho Canova). It ran on CBS for a season, sponsored by Colgate, then moved to NBC in January of 1945 and continued there until May of 1953. The program featured Canova as a country girl transplanted from the mythical hamlet of “Cactus Junction” to Southern California, where she lived with her Aunt Aggie (played at times by Verna Felton and Ruth Perrott) and maid Geranium (Ruby Dandridge). The material on the show was corn as high as an elephant’s eye (though it featured Judy singing both novelty and serious numbers), but is best remembered for its impressive cast of radio pros: Hans Conried (as complaining boarder Mr. Hemingway); Sheldon Leonard (as Joe Crunchmiller, Judy’s cabbie boyfriend); Gerald Mohr (as Humphrey Cooper) and Joseph Kearns (as Benchley Botsford). Gale Gordon, Elvia Allman, George Neise and Sharon Douglas also made occasional appearances.

In the fall of 1943, Judy launched her most successful radio venture with the appropriately titled The Judy Canova Show (though it was briefly known as Rancho Canova). It ran on CBS for a season, sponsored by Colgate, then moved to NBC in January of 1945 and continued there until May of 1953. The program featured Canova as a country girl transplanted from the mythical hamlet of “Cactus Junction” to Southern California, where she lived with her Aunt Aggie (played at times by Verna Felton and Ruth Perrott) and maid Geranium (Ruby Dandridge). The material on the show was corn as high as an elephant’s eye (though it featured Judy singing both novelty and serious numbers), but is best remembered for its impressive cast of radio pros: Hans Conried (as complaining boarder Mr. Hemingway); Sheldon Leonard (as Joe Crunchmiller, Judy’s cabbie boyfriend); Gerald Mohr (as Humphrey Cooper) and Joseph Kearns (as Benchley Botsford). Gale Gordon, Elvia Allman, George Neise and Sharon Douglas also made occasional appearances.

The Judy Canova Show is also remembered for showcasing the work of the one-and-only Mel Blanc…as if he didn’t have enough work in radio at that time. Mel’s primary character was Pedro, Judy’s gardener, who popularized the oft-repeated catchphrase “Pardon me for talking in your face, senorita…” Mel also did double duty as Roscoe Wortle, a fast-talking salesman, and Sylvester—a character whose name and spray-when-he-talked voice were later adopted for the famous Warner Brothers cartoon cat. Mel also recycled Pedro’s voice to use for the same studio’s lightning-quick rodent Speedy Gonzales…and in addition, fell back on Pedro when he voiced the Frito-Lay mascot The Frito Bandito in a series of commercials in the 1970s. (Audiences had become a bit more enlightened by that time, and the ads were quickly pulled after objections were raised by those who felt the stereotype was a bit much.) In later years, Mel and Judy would do a “Ma and Pa” sketch in the latter half of her program.

The Judy Canova Show is also remembered for showcasing the work of the one-and-only Mel Blanc…as if he didn’t have enough work in radio at that time. Mel’s primary character was Pedro, Judy’s gardener, who popularized the oft-repeated catchphrase “Pardon me for talking in your face, senorita…” Mel also did double duty as Roscoe Wortle, a fast-talking salesman, and Sylvester—a character whose name and spray-when-he-talked voice were later adopted for the famous Warner Brothers cartoon cat. Mel also recycled Pedro’s voice to use for the same studio’s lightning-quick rodent Speedy Gonzales…and in addition, fell back on Pedro when he voiced the Frito-Lay mascot The Frito Bandito in a series of commercials in the 1970s. (Audiences had become a bit more enlightened by that time, and the ads were quickly pulled after objections were raised by those who felt the stereotype was a bit much.) In later years, Mel and Judy would do a “Ma and Pa” sketch in the latter half of her program.

Because The Judy Canova Show was a popular Saturday night institution, it was often heavily promoted in tandem with A Day in the Life of Dennis Day, a comedy show also sponsored by Colgate. And years after the show left the airwaves, audiences can still sing the lyrics of Judy’s closing theme:

Because The Judy Canova Show was a popular Saturday night institution, it was often heavily promoted in tandem with A Day in the Life of Dennis Day, a comedy show also sponsored by Colgate. And years after the show left the airwaves, audiences can still sing the lyrics of Judy’s closing theme:

Go to sleep-y, little baby

Go to sleep-y, little baby

When you wake

You’ll patty-patty cake

And ride a shiny little pony

Even before her radio program signed off in 1953, Judy Canova began making inroads on the small screen—with guest appearances on popular shows headlined by Milton Berle and Red Skelton, and roles on such favorites as Make Room for Daddy, Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Love, American Style. Her final TV appearance was in a 1977 episode of The Love Boat. Content in retirement (and proud of her daughter Diana, who at that time was a cast member on the TV sitcom Soap), Judy passed away in 1983 at the age of 69.

Even before her radio program signed off in 1953, Judy Canova began making inroads on the small screen—with guest appearances on popular shows headlined by Milton Berle and Red Skelton, and roles on such favorites as Make Room for Daddy, Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Love, American Style. Her final TV appearance was in a 1977 episode of The Love Boat. Content in retirement (and proud of her daughter Diana, who at that time was a cast member on the TV sitcom Soap), Judy passed away in 1983 at the age of 69.

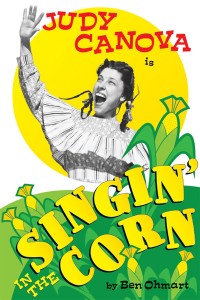

My colleague Ben Ohmart is the author of a very good book about today’s birthday girl. Judy Canova: Singin’ in the Corn—which is available for purchase from Radio Spirits. Plus, you can also check out a December 21, 1946 broadcast of her popular radio sitcom on the RS collection The Voices of Christmas Past. Why not spend some time with the gal affectionately known to her fans as “The Ozark Nightingale” in honor of her natal anniversary?