For generations both old and new, Judy Garland—born Frances Ethel Gumm in Grand Rapids, Minnesota on this date in 1922—will be forever known as Dorothy Gale, the young Kansas girl who gets an opportunity to travel “Over the Rainbow” from her little farm in the Sunflower State to the “Emerald City” in the 1939 movie classic The Wizard of Oz. An accomplishment like this might have been the career highpoint for any other performer…but Judy possessed far too much talent and versatility to rest on those laurels. Garland was frequently listed among the Top Ten box office movie draws during the 1940s, and conquered radio, television, recordings, and the concert stage. It should come as no surprise that in a career that netted Judy an Oscar (a special juvenile trophy), a Tony (in 1952), a Golden Globe (the Cecil B. DeMille Award in 1962), and a Grammy, the American Film Institute named Judy among their ten greatest female stars from classic American cinema in 1999.

Judy Garland was a show business veteran at the age of two-and-a-half. It sounds facetious, but it’s true. She began performing with her sisters Mary Jane (nicknamed “Suzy” or “Suzanne”) and Dorothy Virginia (“Jimmie”) as “The Gumm Sisters” on stage in Minnesota…because father Francis managed a movie theatre that featured vaudeville acts. The family would later relocate to Lancaster, California in 1926, and while the Gumm sisters were enrolled in dance school (in 1928), they became members of the Meglin Kiddies dance troupe (Ethel Meglin operated the school). The sisters’ connection with the Meglin Kiddies would lead to their motion picture debut in the 1929 short The Big Revue (the Gumm trio sang That’s the Good Ol’ Sunny South). Several musical shorts followed, notably A Holiday in Storyland (1930—featuring Judy’s first onscreen solo, Blue Butterfly) and La Fiesta de Santa Barbara (1935).

Judy Garland was a show business veteran at the age of two-and-a-half. It sounds facetious, but it’s true. She began performing with her sisters Mary Jane (nicknamed “Suzy” or “Suzanne”) and Dorothy Virginia (“Jimmie”) as “The Gumm Sisters” on stage in Minnesota…because father Francis managed a movie theatre that featured vaudeville acts. The family would later relocate to Lancaster, California in 1926, and while the Gumm sisters were enrolled in dance school (in 1928), they became members of the Meglin Kiddies dance troupe (Ethel Meglin operated the school). The sisters’ connection with the Meglin Kiddies would lead to their motion picture debut in the 1929 short The Big Revue (the Gumm trio sang That’s the Good Ol’ Sunny South). Several musical shorts followed, notably A Holiday in Storyland (1930—featuring Judy’s first onscreen solo, Blue Butterfly) and La Fiesta de Santa Barbara (1935).

In between movie assignments, The Gumm Sisters toured the vaudeville circuit. In 1934, while playing Chicago’s Oriental Theater, comedian George Jessel suggested that the trio change their billing to…well, anything more appealing than “Gumm.” There are endless variations on how the sisters decided on “Garland” (one story suggests that they were inspired by the last name of Carole Lombard’s character in Twentieth Century [1934]), but “Garland” it became. The act broke up in August of 1935, when Suzanne flew to Reno, Nevada to tie the knot with musician Lee Kahn. (Judy, incidentally, decided on her new first name after being inspired by the title of a popular Hoagy Carmichael tune.)

In between movie assignments, The Gumm Sisters toured the vaudeville circuit. In 1934, while playing Chicago’s Oriental Theater, comedian George Jessel suggested that the trio change their billing to…well, anything more appealing than “Gumm.” There are endless variations on how the sisters decided on “Garland” (one story suggests that they were inspired by the last name of Carole Lombard’s character in Twentieth Century [1934]), but “Garland” it became. The act broke up in August of 1935, when Suzanne flew to Reno, Nevada to tie the knot with musician Lee Kahn. (Judy, incidentally, decided on her new first name after being inspired by the title of a popular Hoagy Carmichael tune.)

Judy signed a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1935 on the strength of a performance of Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart and Eli, Eli for MGM’s Louis B. Mayer. The studio got a bundle of talent with the acquisition of Garland but was often perplexed about what to do with her. At thirteen, she was older than the usual child star, but was too young for adult roles. (Mayer, charming as he was, also fretted that Judy was not as glamorous as the rest of MGM’s female stars, reportedly calling her his “little hunchback.”) After being loaned to 20th Century-Fox for 1936’s Pigskin Parade, her first role for MGM would be in a 1936 musical short, Every Sunday, which also featured a performer that would make a name for herself as Universal’s resident child talent: Deanna Durbin. Garland’s first MGM feature film appearance would be a memorable one, performing You Made Me Love You to a photograph of the studio’s “king,” Clark Gable, in Broadway Melody of 1938 (1937). From there, Judy landed roles in efforts like Everybody Sing (1938) and Listen, Darling (1938).

Judy Garland’s role in Thoroughbreds Don’t Cry (1937) would be the first of ten feature films she made with MGM’s other big child star, Mickey Rooney (including specialty bits in Thousands Cheer [1943] and Words and Music [1948]). Their “let’s-put-on-a-show” musicals like Babes in Arms (1939), Strike Up the Band (1940), Babes on Broadway (1941), and Girl Crazy (1943) proved quite popular with moviegoers, and Judy also appeared as “Betsy Booth” in three of the entries in Mickey’s Andy Hardy series: Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938), Andy Hardy Meets Debutante (1940), and Life Begins for Andy Hardy (1941). Her work in Wizard and Babes netted Garland her only Oscar, but by the 1940s she was transitioning to more adult roles with Little Nellie Kelly (1940) and Ziegfeld Girl (1941). Kelly was the film in which she received her first “grown-up” kiss…and was required to do her first death scene. (Sorry for the spoiler.)

Judy Garland’s role in Thoroughbreds Don’t Cry (1937) would be the first of ten feature films she made with MGM’s other big child star, Mickey Rooney (including specialty bits in Thousands Cheer [1943] and Words and Music [1948]). Their “let’s-put-on-a-show” musicals like Babes in Arms (1939), Strike Up the Band (1940), Babes on Broadway (1941), and Girl Crazy (1943) proved quite popular with moviegoers, and Judy also appeared as “Betsy Booth” in three of the entries in Mickey’s Andy Hardy series: Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938), Andy Hardy Meets Debutante (1940), and Life Begins for Andy Hardy (1941). Her work in Wizard and Babes netted Garland her only Oscar, but by the 1940s she was transitioning to more adult roles with Little Nellie Kelly (1940) and Ziegfeld Girl (1941). Kelly was the film in which she received her first “grown-up” kiss…and was required to do her first death scene. (Sorry for the spoiler.)

Me and My Gal (1942) was the first of six films Judy Garland appeared in with MGM’s resident dance dynamo, Gene Kelly (among their memorable team-ups are The Pirate [1948] and Summer Stock [1950]). Judy’s other 40s hits include Presenting Lily Mars (1943) and The Harvey Girls (1946—featuring the Oscar-winning song On the Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe). However, her best-known film from that period is inarguably Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), which was directed by her soon-to-be husband Vincente Minnelli. A heartwarming tale of a family whose lives are turned upside down when the father gets news he’s being relocated to New York City. St. Louis introduced three Garland song standards: The Trolley Song, The Boy Next Door, and the Yuletide classic Have Yourself a Little Merry Christmas. Judy and Vincente would tie the knot after St. Louis was completed, and though the union came to an end in 1951, the couple worked on several additional films together, including Garland’s first straight dramatic film The Clock in 1945.

Me and My Gal (1942) was the first of six films Judy Garland appeared in with MGM’s resident dance dynamo, Gene Kelly (among their memorable team-ups are The Pirate [1948] and Summer Stock [1950]). Judy’s other 40s hits include Presenting Lily Mars (1943) and The Harvey Girls (1946—featuring the Oscar-winning song On the Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe). However, her best-known film from that period is inarguably Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), which was directed by her soon-to-be husband Vincente Minnelli. A heartwarming tale of a family whose lives are turned upside down when the father gets news he’s being relocated to New York City. St. Louis introduced three Garland song standards: The Trolley Song, The Boy Next Door, and the Yuletide classic Have Yourself a Little Merry Christmas. Judy and Vincente would tie the knot after St. Louis was completed, and though the union came to an end in 1951, the couple worked on several additional films together, including Garland’s first straight dramatic film The Clock in 1945.

A star of Judy Garland’s magnitude would certainly make the rounds of network radio, and she made one of her first appearances over the ether on a 1935 broadcast of Shell Chateau. Judy’s films would be dramatized on shows like The Lux Radio Theatre and The Gulf/Lady Esther Screen Guild Theatre, and Garland also made a memorable appearance on Suspense with the classic “Drive-In” (11/21/46). As a dues-paying MGM employee, Garland would appear on Good News of 1938/1939 on multiple occasions, and during WW2 was a favorite on such AFRS mainstays as Command Performance, G.I. Journal, and Mail Call. Radio stars learned that inviting Judy on their programs guaranteed a half-hour of unadulterated entertainment, and big names like Edgar Bergen, Bob Hope, George Jessel, Al Jolson, Danny Kaye, and Jack Oakie made her most welcome. The Old Groaner himself, Bing Crosby, always enjoyed having Judy as guest. Garland not only appeared on his Philco Radio Time, but at a time when Judy was struggling with personal problems in her life, Der Bingle called her “guest star” on over a dozen of the broadcasts he did for Chesterfield/General Electric between 1949 and 1952. (An October 30, 1952 show even has Judy Garland going solo on Bing’s program—a possible audition for a Garland radio series?)

A star of Judy Garland’s magnitude would certainly make the rounds of network radio, and she made one of her first appearances over the ether on a 1935 broadcast of Shell Chateau. Judy’s films would be dramatized on shows like The Lux Radio Theatre and The Gulf/Lady Esther Screen Guild Theatre, and Garland also made a memorable appearance on Suspense with the classic “Drive-In” (11/21/46). As a dues-paying MGM employee, Garland would appear on Good News of 1938/1939 on multiple occasions, and during WW2 was a favorite on such AFRS mainstays as Command Performance, G.I. Journal, and Mail Call. Radio stars learned that inviting Judy on their programs guaranteed a half-hour of unadulterated entertainment, and big names like Edgar Bergen, Bob Hope, George Jessel, Al Jolson, Danny Kaye, and Jack Oakie made her most welcome. The Old Groaner himself, Bing Crosby, always enjoyed having Judy as guest. Garland not only appeared on his Philco Radio Time, but at a time when Judy was struggling with personal problems in her life, Der Bingle called her “guest star” on over a dozen of the broadcasts he did for Chesterfield/General Electric between 1949 and 1952. (An October 30, 1952 show even has Judy Garland going solo on Bing’s program—a possible audition for a Garland radio series?)

As magical as Judy Garland’s life onscreen and before the radio microphones seemed, her personal life was occasionally fraught with turmoil. Though her movie successes included at this time Easter Parade (1948; with Fred Astaire) and In the Good Old Summertime (1949), Judy would end up being replaced on three feature films: The Barkleys of Broadway (1949), Annie Get Your Gun (1950), and Royal Wedding (1951). She left MGM in 1951 and embarked on a series of concert bookings in the United Kingdom, with her appearance at Manhattan’s famed Palace Theatre in October of that year hailed as “one of the greatest personal triumphs in show business history.” Her stage work was singled out for a special Tony Award, and in 1954 Judy began work on her “comeback” film, A Star is Born.

As magical as Judy Garland’s life onscreen and before the radio microphones seemed, her personal life was occasionally fraught with turmoil. Though her movie successes included at this time Easter Parade (1948; with Fred Astaire) and In the Good Old Summertime (1949), Judy would end up being replaced on three feature films: The Barkleys of Broadway (1949), Annie Get Your Gun (1950), and Royal Wedding (1951). She left MGM in 1951 and embarked on a series of concert bookings in the United Kingdom, with her appearance at Manhattan’s famed Palace Theatre in October of that year hailed as “one of the greatest personal triumphs in show business history.” Her stage work was singled out for a special Tony Award, and in 1954 Judy began work on her “comeback” film, A Star is Born.

You could theoretically argue with Garland fans until the end of time as to what her greatest motion picture triumph was. I love Wizard of Oz (a childhood favorite), but others will make strong cases for Meet Me in St. Louis and A Star is Born. Star, which had been filmed previously in 1937 (and technically, before that as What Price Hollywood? in 1932), opened in September of 1954 to both enthusiastic audience and critical acclaim. (Then the studio went in and edited it with a chainsaw, ensuring that Star would fail to make back its cost.) Judy was nominated for a Best Actress Academy Award…and though expected by many to win, she sadly watched Grace Kelly walk off with the prize for her turn in The Country Girl (1954). (Judy’s loss prompted Groucho Marx to remark that it was “the biggest robbery since Brink’s.”) Undaunted, Garland began to explore avenues on the small screen, beginning with a well-received appearance on Ford Star Jubilee, which was the first full-scale color telecast on CBS. Judy did a series of follow-up specials throughout the years before committing to the rigors of a weekly TV show in the fall of 1963. (She had quite a few debts at the time, which convinced her to go back on an earlier declaration that she’d never do weekly TV.)

You could theoretically argue with Garland fans until the end of time as to what her greatest motion picture triumph was. I love Wizard of Oz (a childhood favorite), but others will make strong cases for Meet Me in St. Louis and A Star is Born. Star, which had been filmed previously in 1937 (and technically, before that as What Price Hollywood? in 1932), opened in September of 1954 to both enthusiastic audience and critical acclaim. (Then the studio went in and edited it with a chainsaw, ensuring that Star would fail to make back its cost.) Judy was nominated for a Best Actress Academy Award…and though expected by many to win, she sadly watched Grace Kelly walk off with the prize for her turn in The Country Girl (1954). (Judy’s loss prompted Groucho Marx to remark that it was “the biggest robbery since Brink’s.”) Undaunted, Garland began to explore avenues on the small screen, beginning with a well-received appearance on Ford Star Jubilee, which was the first full-scale color telecast on CBS. Judy did a series of follow-up specials throughout the years before committing to the rigors of a weekly TV show in the fall of 1963. (She had quite a few debts at the time, which convinced her to go back on an earlier declaration that she’d never do weekly TV.)

The Judy Garland Show was adored by critics and would win four Emmy Award nominations (including Best Variety Series), but it had the misfortune of being scheduled up against NBC’s Top Ten favorite Bonanza on Sunday nights. It was cancelled after 26 telecasts. Judy’s continued concert successes—her April 23, 1961 Carnegie Hall appearance spawned the Grammy-winning double LP Judy at Carnegie Hall, which even today remains a best seller—kept her in the public eye. She even made the occasional feature film appearance in Judgment at Nuremberg (1961—a powerful performance that would win her last Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress), Gay Purr-ee (1962—an animated feature where she provided the singing and speaking voice of the movie’s feline hero), and A Child is Waiting (1963). Judy’s final feature film was 1963’s I Could Go on Singing; she had been scheduled to play a role in Valley of the Dolls (1967), but this would go the way of previous unfinished projects. Judy Garland left this world far too soon at the age of 47 on June 22, 1969.

The Judy Garland Show was adored by critics and would win four Emmy Award nominations (including Best Variety Series), but it had the misfortune of being scheduled up against NBC’s Top Ten favorite Bonanza on Sunday nights. It was cancelled after 26 telecasts. Judy’s continued concert successes—her April 23, 1961 Carnegie Hall appearance spawned the Grammy-winning double LP Judy at Carnegie Hall, which even today remains a best seller—kept her in the public eye. She even made the occasional feature film appearance in Judgment at Nuremberg (1961—a powerful performance that would win her last Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress), Gay Purr-ee (1962—an animated feature where she provided the singing and speaking voice of the movie’s feline hero), and A Child is Waiting (1963). Judy’s final feature film was 1963’s I Could Go on Singing; she had been scheduled to play a role in Valley of the Dolls (1967), but this would go the way of previous unfinished projects. Judy Garland left this world far too soon at the age of 47 on June 22, 1969.

Judy Garland, in later years, was a much-in-demand guest on the talk show circuit, where she demonstrated that, despite her struggles with offstage demons, she was the true embodiment of the word “entertainer.” Here at Radio Spirits, Ms. Garland is one of several stars showcased on the 4-DVD collection Hollywood’s Greatest Screen Legends…but your best bet for Maximum Garland is a purchase of the 3-CD George Gershwin Collection; Judy and Mickey Rooney’s title duet from Strike Up the Band is included, as is a hit duet with Bing Crosby (Mine) and three tunes from Girl Crazy: Embraceable You, Bidin’ My Time, and the standard I Got Rhythm (another duet with the Mick). You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet! Showstoppers features four Judy favorites—Over the Rainbow, The Trolley Song, The Man That Got Away, and her title duet with Gene Kelly from 1942’s Me and My Gal (For Me and My Gal is also available on Their Shining Hour – The Road to Victory). Judy duets with Gene on When You Wore a Tulip and solos on Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart (her audition song!) on You Make Me Feel So Young, and two of her favorites, The Boy Next Door and Dear Mr. Gable, are front and center on With a Song in My Heart: Hooray for Hollywood. Finally…it’s not too early to stock up on Christmas gifts: Legends: The Christmas Collection offers Judy Garland’s immortal rendition of Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas. Happy birthday, Judy!

Judy Garland, in later years, was a much-in-demand guest on the talk show circuit, where she demonstrated that, despite her struggles with offstage demons, she was the true embodiment of the word “entertainer.” Here at Radio Spirits, Ms. Garland is one of several stars showcased on the 4-DVD collection Hollywood’s Greatest Screen Legends…but your best bet for Maximum Garland is a purchase of the 3-CD George Gershwin Collection; Judy and Mickey Rooney’s title duet from Strike Up the Band is included, as is a hit duet with Bing Crosby (Mine) and three tunes from Girl Crazy: Embraceable You, Bidin’ My Time, and the standard I Got Rhythm (another duet with the Mick). You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet! Showstoppers features four Judy favorites—Over the Rainbow, The Trolley Song, The Man That Got Away, and her title duet with Gene Kelly from 1942’s Me and My Gal (For Me and My Gal is also available on Their Shining Hour – The Road to Victory). Judy duets with Gene on When You Wore a Tulip and solos on Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart (her audition song!) on You Make Me Feel So Young, and two of her favorites, The Boy Next Door and Dear Mr. Gable, are front and center on With a Song in My Heart: Hooray for Hollywood. Finally…it’s not too early to stock up on Christmas gifts: Legends: The Christmas Collection offers Judy Garland’s immortal rendition of Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas. Happy birthday, Judy!

The protagonist of The Big Sleep was a private detective named Philip Marlowe, who figured heavily in Chandler’s follow-up novel, Farewell, My Lovely, in 1940. Lovely would be adapted for two motion picture screenplays: an RKO production in their popular “Falcon” series (starring George Sanders) entitled The Falcon Takes Over (1942), and a Dick Powell film destined to become a noir classic (also produced at RKO) called Murder, My Sweet (1944). With Sweet and the silver screen adaptations of Chandler’s Sleep in 1946 (starring Humphrey Bogart as Marlowe) and The Lady in the Lake (with Robert Montgomery) the following year, it was only a matter of time before Chandler’s “white knight in a trench coat” got his own radio series (especially after Sweet was well-received on a Lux Radio Theatre broadcast in 1945). The Adventures of Philip Marlowe made its debut over the ether on this date in 1947.

The protagonist of The Big Sleep was a private detective named Philip Marlowe, who figured heavily in Chandler’s follow-up novel, Farewell, My Lovely, in 1940. Lovely would be adapted for two motion picture screenplays: an RKO production in their popular “Falcon” series (starring George Sanders) entitled The Falcon Takes Over (1942), and a Dick Powell film destined to become a noir classic (also produced at RKO) called Murder, My Sweet (1944). With Sweet and the silver screen adaptations of Chandler’s Sleep in 1946 (starring Humphrey Bogart as Marlowe) and The Lady in the Lake (with Robert Montgomery) the following year, it was only a matter of time before Chandler’s “white knight in a trench coat” got his own radio series (especially after Sweet was well-received on a Lux Radio Theatre broadcast in 1945). The Adventures of Philip Marlowe made its debut over the ether on this date in 1947. Academy Award-winner Van Heflin played Marlowe in this first radio incarnation of Chandler’s detective, though as critic John Crosby noted in a 1947 review for The Oakland Tribune, “No matter who plays Marlowe, he remains a cynical cuss who complains that he could be quite a nice guy if everyone else in the world weren’t such a 14-karat heel. This somewhat sweeping indictment is understandable in Marlowe’s case; he gets mixed up with the funniest people.” Heflin’s interpretation of Marlowe is a most interesting one and it’s conceivable that after thirteen episodes (Marlowe was a summer replacement for Bob Hope’s Pepsodent show) the actor could have made a further go at portraying the shamus. Raymond Chandler, however, wasn’t a fan of Heflin’s take on his creation. He complained that it was “thoroughly flat” in a letter to Perry Mason creator Erle Stanley Gardner. (Chandler studied many of the Mason stories before embarking on his writing own ambitions.) Anyway, MGM—Van Heflin’s employer—had other plans for their star.

Academy Award-winner Van Heflin played Marlowe in this first radio incarnation of Chandler’s detective, though as critic John Crosby noted in a 1947 review for The Oakland Tribune, “No matter who plays Marlowe, he remains a cynical cuss who complains that he could be quite a nice guy if everyone else in the world weren’t such a 14-karat heel. This somewhat sweeping indictment is understandable in Marlowe’s case; he gets mixed up with the funniest people.” Heflin’s interpretation of Marlowe is a most interesting one and it’s conceivable that after thirteen episodes (Marlowe was a summer replacement for Bob Hope’s Pepsodent show) the actor could have made a further go at portraying the shamus. Raymond Chandler, however, wasn’t a fan of Heflin’s take on his creation. He complained that it was “thoroughly flat” in a letter to Perry Mason creator Erle Stanley Gardner. (Chandler studied many of the Mason stories before embarking on his writing own ambitions.) Anyway, MGM—Van Heflin’s employer—had other plans for their star. After a year’s vacation, Philip Marlowe returned for a CBS series that premiered on September 26, 1948. The actor who put on Marlowe’s trench coat was Gerald Mohr, in a production overseen by director-producer Norman Macdonnell. (Macdonnell’s Marlowe was a favorite of CBS chairman William S. Paley, who pressed the network’s creative team to come up with a “Philip Marlowe in the early West.”) Mohr also had Chandler’s approval. The author noted that Gerald’s voice “at least packed personality.” (Okay, so Chandler wasn’t exactly effusive with the praise.) CBS’s The Adventures of Philip Marlowe was an audience favorite featuring a memorable opening. Mohr’s Marlowe would bark: “Get this and get it straight—crime is a sucker’s road, and those who travel it end up in the gutter, the prison, or an early grave…”

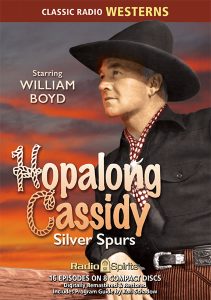

After a year’s vacation, Philip Marlowe returned for a CBS series that premiered on September 26, 1948. The actor who put on Marlowe’s trench coat was Gerald Mohr, in a production overseen by director-producer Norman Macdonnell. (Macdonnell’s Marlowe was a favorite of CBS chairman William S. Paley, who pressed the network’s creative team to come up with a “Philip Marlowe in the early West.”) Mohr also had Chandler’s approval. The author noted that Gerald’s voice “at least packed personality.” (Okay, so Chandler wasn’t exactly effusive with the praise.) CBS’s The Adventures of Philip Marlowe was an audience favorite featuring a memorable opening. Mohr’s Marlowe would bark: “Get this and get it straight—crime is a sucker’s road, and those who travel it end up in the gutter, the prison, or an early grave…” For his portrayal of Marlowe, Gerald Mohr was chosen by Radio-Television Magazine as their Most Popular Male Actor. The Adventures of Philip Marlowe ran two years (it was a sustained series), but was briefly revived in the summer of 1951 (as a replacement for Hopalong Cassidy) with Mohr reprising his role. “The Sound and the Unsound” (09/15/51) would be Philip Marlowe’s radio swan song, but he continued to take cases on TV (for example, Philip Carey played the detective in a 1959-60 TV series for ABC) and in movies (interpreted by thespians such as James Garner and Elliott Gould).

For his portrayal of Marlowe, Gerald Mohr was chosen by Radio-Television Magazine as their Most Popular Male Actor. The Adventures of Philip Marlowe ran two years (it was a sustained series), but was briefly revived in the summer of 1951 (as a replacement for Hopalong Cassidy) with Mohr reprising his role. “The Sound and the Unsound” (09/15/51) would be Philip Marlowe’s radio swan song, but he continued to take cases on TV (for example, Philip Carey played the detective in a 1959-60 TV series for ABC) and in movies (interpreted by thespians such as James Garner and Elliott Gould). For many years, only three broadcasts from the original 1947 Philip Marlowe survived the ravages of time and neglect…but two additional transcriptions eventually resurfaced, and you’ll find all five of those Van Heflin episodes on our The Adventures of Philip Marlowe collection. Gerald Mohr’s Marlowe is represented on that set, too—not to mention Lonely Canyons, Night Tide, and Sucker’s Road. There are broadcasts of Mohr’s Marlowe on our potpourri compilations Great Radio Detectives (“The Uneasy Head”) and Radio Classics: Selected by Greg Bell (“The Quiet Magpie”), and to round out your collection, Radio Spirits highly recommends DVD purchases of Farewell, My Lovely (1975) and The Big Sleep (1978)—both starring Robert Mitchum as our favorite shamus. In the words of Raymond Chandler: “…down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. He is the hero; he is everything.” He’s Philip Marlowe!

For many years, only three broadcasts from the original 1947 Philip Marlowe survived the ravages of time and neglect…but two additional transcriptions eventually resurfaced, and you’ll find all five of those Van Heflin episodes on our The Adventures of Philip Marlowe collection. Gerald Mohr’s Marlowe is represented on that set, too—not to mention Lonely Canyons, Night Tide, and Sucker’s Road. There are broadcasts of Mohr’s Marlowe on our potpourri compilations Great Radio Detectives (“The Uneasy Head”) and Radio Classics: Selected by Greg Bell (“The Quiet Magpie”), and to round out your collection, Radio Spirits highly recommends DVD purchases of Farewell, My Lovely (1975) and The Big Sleep (1978)—both starring Robert Mitchum as our favorite shamus. In the words of Raymond Chandler: “…down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. He is the hero; he is everything.” He’s Philip Marlowe!