Happy Birthday, Charles Boyer!

Any self-respecting impressionist attempting to imitate actor Charles Boyer—born in Figeac, Lot, France on this date in 1899—had only to utter this phrase: “Come wiz me to the Cazbah…” It’s a reference to one of Charles’ best-known movie roles: that of master thief Pepe le Moko, a fugitive hiding out in the famed Casbah section (Casbah translates as “fortress” or “citadel”) of Algiers in the 1938 movie of the same name. Algiers was a remake of a 1937 French film, Pepe le Moko, but the Boyer version (with co-star Hedy Lamarr) would be the film that not only launched a thousand Boyer impressions but inspired the Warner Brothers cartoon character Pepe le Pew. (You shouldn’t be too surprised that, like “Play it again, Sam” and “Me Tarzan, you Jane,” the line “Come with me to the Casbah” is not actually spoken in the film.)

As for the star of Algiers, Charles Boyer was offscreen a private and bookish individual—a persona completely at odds with his silver screen reputation as a suave romantic idol. As a child, he overcame an innate shyness by developing a fondness for the theatre and movies at the age of 11. His earliest performances were for injured soldiers during the First World War, where he worked as a hospital orderly. While studying at the Sorbonne (where he would eventually earn a degree in philosophy), Boyer waited for an opportunity to pursue acting at the Paris Conservatory. Charles was committed to an acting career at this point in his life, and his ability to quickly memorize lines won him the leading role in a theatrical production in 1920. Throughout that decade, Boyer not only worked regularly on stage, he appeared in several silent films as well — beginning with L’homme du large (1920).

As for the star of Algiers, Charles Boyer was offscreen a private and bookish individual—a persona completely at odds with his silver screen reputation as a suave romantic idol. As a child, he overcame an innate shyness by developing a fondness for the theatre and movies at the age of 11. His earliest performances were for injured soldiers during the First World War, where he worked as a hospital orderly. While studying at the Sorbonne (where he would eventually earn a degree in philosophy), Boyer waited for an opportunity to pursue acting at the Paris Conservatory. Charles was committed to an acting career at this point in his life, and his ability to quickly memorize lines won him the leading role in a theatrical production in 1920. Throughout that decade, Boyer not only worked regularly on stage, he appeared in several silent films as well — beginning with L’homme du large (1920).

Charles Boyer’s deep voice was tailor-made for talking pictures and he began to make appearances in films like Paramount’s The Man from Yesterday (1932), MGM’s Red-Headed Woman (1932), and scored the starring role in Fritz Lang’s Liliom for Fox Film in 1934 (later remade as the 1956 musical Carousel). He played leading man to Loretta Young in Caravan (1934) and Claudette Colbert (his Man from Yesterday co-star) in Private Worlds (1935). Boyer’s preference may have been for French feature films at this time, but after a string of U.S. hits like Break of Hearts (1935; with Katharine Hepburn), The Garden of Allah (1936; Marlene Dietrich), History is Made at Night (1937; Jean Arthur), Conquest (1937; Greta Garbo), and Love Affair (1939; Irene Dunne), Charles’ status as a romantic leading man could no longer be ignored. (Love Affair was purportedly his favorite among his many movies.)

Charles Boyer’s deep voice was tailor-made for talking pictures and he began to make appearances in films like Paramount’s The Man from Yesterday (1932), MGM’s Red-Headed Woman (1932), and scored the starring role in Fritz Lang’s Liliom for Fox Film in 1934 (later remade as the 1956 musical Carousel). He played leading man to Loretta Young in Caravan (1934) and Claudette Colbert (his Man from Yesterday co-star) in Private Worlds (1935). Boyer’s preference may have been for French feature films at this time, but after a string of U.S. hits like Break of Hearts (1935; with Katharine Hepburn), The Garden of Allah (1936; Marlene Dietrich), History is Made at Night (1937; Jean Arthur), Conquest (1937; Greta Garbo), and Love Affair (1939; Irene Dunne), Charles’ status as a romantic leading man could no longer be ignored. (Love Affair was purportedly his favorite among his many movies.)

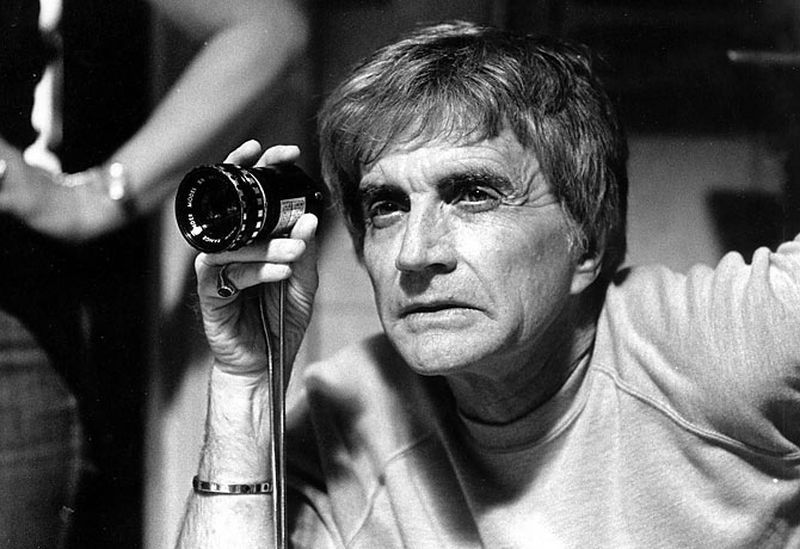

Charles Boyer may have portrayed the great lover onscreen…but offscreen, he refused to wear his toupee (Boyer had been losing his hair since his twenties) and made no effort to conceal a rather pronounced paunch. (The story goes that his All This, and Heaven, Too leading lady Bette Davis failed to recognize him and tried to have him ejected from the set.) But movies are magic, ma chère; Charlie continued to make female moviegoers swoon with film successes such as Back Street (1941), Hold Back the Dawn (1941—my favorite of Boyer’s films), The Constant Nymph (1943), Gaslight (1944), Confidential Agent (1945), Cluny Brown (1946), and A Woman’s Vengeance (1947). Boyer would win an honorary Academy Award in 1943 for his work in establishing Los Angeles’ French Research Foundation. This somewhat compensated for the fact that, despite being nominated four separate times for an acting Oscar (Conquest, Algiers, Gaslight, and 1961’s Fanny), the actor never got a trophy to put on his mantle.

Charles Boyer may have portrayed the great lover onscreen…but offscreen, he refused to wear his toupee (Boyer had been losing his hair since his twenties) and made no effort to conceal a rather pronounced paunch. (The story goes that his All This, and Heaven, Too leading lady Bette Davis failed to recognize him and tried to have him ejected from the set.) But movies are magic, ma chère; Charlie continued to make female moviegoers swoon with film successes such as Back Street (1941), Hold Back the Dawn (1941—my favorite of Boyer’s films), The Constant Nymph (1943), Gaslight (1944), Confidential Agent (1945), Cluny Brown (1946), and A Woman’s Vengeance (1947). Boyer would win an honorary Academy Award in 1943 for his work in establishing Los Angeles’ French Research Foundation. This somewhat compensated for the fact that, despite being nominated four separate times for an acting Oscar (Conquest, Algiers, Gaslight, and 1961’s Fanny), the actor never got a trophy to put on his mantle.

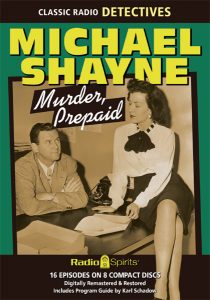

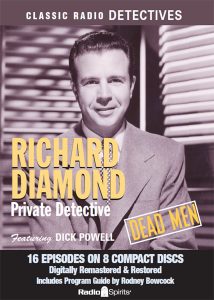

Charles Boyer’s radio career began back in the late 1930s with regular appearances on Hollywood Playhouse. The actor’s silver screen stardom would lead him to make the rounds—often reprising his movie roles, and sometimes appearing in original productions—on such popular programs as The Cavalcade of America, The Gulf/Lady Esther Screen Guild Theatre, Family Theatre, The Hallmark Hall of Fame, Hallmark Playhouse, The Lux Radio Theatre, The Philco Radio Hall of Fame, Screen Directors’ Playhouse, The Silver Theatre, and Suspense. Charles’ romantic reputation in the flickers also made him the perfect foil for comedians and personalities like Edgar Bergen, Bob Burns, George Burns & Gracie Allen, Eddie Cantor, Jimmy Durante, Bob Hope, Al Jolson, and Francis Langford…while also making time to guest star on Amos ‘n’ Andy, The Big Show, Command Performance, A Date with Judy, and Mail Call.

Charles Boyer’s radio career began back in the late 1930s with regular appearances on Hollywood Playhouse. The actor’s silver screen stardom would lead him to make the rounds—often reprising his movie roles, and sometimes appearing in original productions—on such popular programs as The Cavalcade of America, The Gulf/Lady Esther Screen Guild Theatre, Family Theatre, The Hallmark Hall of Fame, Hallmark Playhouse, The Lux Radio Theatre, The Philco Radio Hall of Fame, Screen Directors’ Playhouse, The Silver Theatre, and Suspense. Charles’ romantic reputation in the flickers also made him the perfect foil for comedians and personalities like Edgar Bergen, Bob Burns, George Burns & Gracie Allen, Eddie Cantor, Jimmy Durante, Bob Hope, Al Jolson, and Francis Langford…while also making time to guest star on Amos ‘n’ Andy, The Big Show, Command Performance, A Date with Judy, and Mail Call.

Regarding his work on the radio, a trade publication from 1940 reported: “It is an open secret that he doesn’t like the present policy of a different story and characters each week. Boyer would prefer a program in which he could develop a permanent characterization.” Charles Boyer would get his wish with Presenting Charles Boyer, a dramatic series that premiered in the summer of 1950 as a replacement for Fibber McGee & Molly. (It would exit the airwaves in October that same year.) Boyer played a charming rogue named Michel who, according to announcer Don Stanley, “belongs to that royal line of adventurers whose titles are stitched on the fabric of their own imaginations but who’d willingly give up any title for a moment of romance or a spot of cash.” By this point in his career, Charles was starting to gravitate more toward character roles and did so quite successfully with movies like The 13th Letter (1951), The First Legion (1951), The Happy Time (1952), and The Earrings of Madame De… (1953).

Regarding his work on the radio, a trade publication from 1940 reported: “It is an open secret that he doesn’t like the present policy of a different story and characters each week. Boyer would prefer a program in which he could develop a permanent characterization.” Charles Boyer would get his wish with Presenting Charles Boyer, a dramatic series that premiered in the summer of 1950 as a replacement for Fibber McGee & Molly. (It would exit the airwaves in October that same year.) Boyer played a charming rogue named Michel who, according to announcer Don Stanley, “belongs to that royal line of adventurers whose titles are stitched on the fabric of their own imaginations but who’d willingly give up any title for a moment of romance or a spot of cash.” By this point in his career, Charles was starting to gravitate more toward character roles and did so quite successfully with movies like The 13th Letter (1951), The First Legion (1951), The Happy Time (1952), and The Earrings of Madame De… (1953).

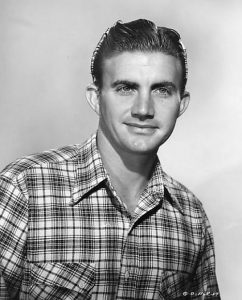

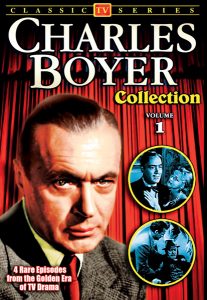

Along with David Niven, Dick Powell, and Ida Lupino, Charles Boyer was part of the founding quartet of stars who appeared as both host and occasional performer on TV’s Four Star Playhouse. This popular television anthology ran for four seasons and was produced by the aptly named Four Star Productions. Four Star would continue in the small screen business with several successful hits, including Dick Powell’s Zane Grey Theatre, Burke’s Law, and The Big Valley. Niven and Boyer would later comprise two-thirds of the cast of another of the company’s boob tube offerings, The Rogues, a most entertaining comedy-drama that sadly lasted but a single season (despite winning a Golden Globe Award as Best Television Series in 1964). (The premise was that Niven, Boyer, and Gig Young were a trio of con artists who used their talents for niceness to shake down unscrupulously wealthy “marks.”)

Along with David Niven, Dick Powell, and Ida Lupino, Charles Boyer was part of the founding quartet of stars who appeared as both host and occasional performer on TV’s Four Star Playhouse. This popular television anthology ran for four seasons and was produced by the aptly named Four Star Productions. Four Star would continue in the small screen business with several successful hits, including Dick Powell’s Zane Grey Theatre, Burke’s Law, and The Big Valley. Niven and Boyer would later comprise two-thirds of the cast of another of the company’s boob tube offerings, The Rogues, a most entertaining comedy-drama that sadly lasted but a single season (despite winning a Golden Globe Award as Best Television Series in 1964). (The premise was that Niven, Boyer, and Gig Young were a trio of con artists who used their talents for niceness to shake down unscrupulously wealthy “marks.”)

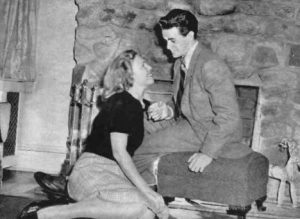

Charles Boyer continued in his senior roles throughout the 1960s/1970s with appearances in feature films like Fanny and The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (both 1961), How to Steal a Million (1966), Barefoot in the Park (1967), Lost Horizon (1973), and Stavisky… (1974). His final feature film was 1976’s A Matter of Time. Although moviegoers saw him alongside a variety of leading ladies throughout his cinematic career, in real life he was dedicated to only one woman—British actress Pat Paterson, whom he had wed in 1934. When Pat succumbed to cancer in 1978, Charles took his own life two days later with an overdose of barbiturates at the age of 79.

Charles Boyer continued in his senior roles throughout the 1960s/1970s with appearances in feature films like Fanny and The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (both 1961), How to Steal a Million (1966), Barefoot in the Park (1967), Lost Horizon (1973), and Stavisky… (1974). His final feature film was 1976’s A Matter of Time. Although moviegoers saw him alongside a variety of leading ladies throughout his cinematic career, in real life he was dedicated to only one woman—British actress Pat Paterson, whom he had wed in 1934. When Pat succumbed to cancer in 1978, Charles took his own life two days later with an overdose of barbiturates at the age of 79.

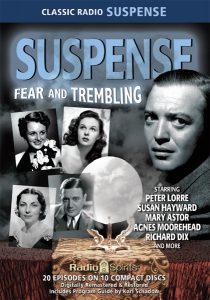

“In America, when you have an accent, in the mind of the people they associate you with kissing hands and being gallant,” Charles Boyer once remarked to an interviewer. “I think that has harmed me, just as it has harmed me to be followed and plagued by a line I never said.” But you need not worry! Radio Spirits’ offerings featuring our birthday celebrant are free of propositions to follow him to the Casbah. In our Suspense collection Wages of Sin, Boyer is the guest on “radio’s outstanding theatre of thrills” with a May 17, 1951 presentation of “Another Man’s Poison.” On the DVD side, we offer two collections of Four Star Playhouse (Volume 1 and Volume 4) containing a total of eight of Charles’ appearances from the popular TV anthology. Additionally, Boyer is well-represented on Four Star Playhouse, Volume 4 with a presentation of “The Man in the Cellar” (09/30/54). Happy birthday to one of our favorite Hollywood legends!

“In America, when you have an accent, in the mind of the people they associate you with kissing hands and being gallant,” Charles Boyer once remarked to an interviewer. “I think that has harmed me, just as it has harmed me to be followed and plagued by a line I never said.” But you need not worry! Radio Spirits’ offerings featuring our birthday celebrant are free of propositions to follow him to the Casbah. In our Suspense collection Wages of Sin, Boyer is the guest on “radio’s outstanding theatre of thrills” with a May 17, 1951 presentation of “Another Man’s Poison.” On the DVD side, we offer two collections of Four Star Playhouse (Volume 1 and Volume 4) containing a total of eight of Charles’ appearances from the popular TV anthology. Additionally, Boyer is well-represented on Four Star Playhouse, Volume 4 with a presentation of “The Man in the Cellar” (09/30/54). Happy birthday to one of our favorite Hollywood legends!