“Extra, extra—get your Illustrated Press!”

The Golden Age of Radio—and this may be a good or bad thing, depending upon your opinion of the Fourth Estate—was a regular breeding ground for newspaper folk. Superheroes like The Green Hornet and Superman were journalists when they weren’t out fighting crime (the “Har-nut” was newspaper editor Britt Reid, and Superman’s Clark Kent punched a time clock at The Daily Planet). The aural medium also brought us the dramatic sagas of Front Page Farrell and Casey, Crime Photographer, not to mention Chicago reporter Randy Stone of Night Beat fame. Real-life tales of newspaper scoops were even featured on the anthology program The Big Story. Head-and-shoulders above them all, of course, was Big Town—which premiered over the airwaves on this date in 1937.

Big Town was created as a vehicle for actor Edward G. Robinson. Eddie G. had actually played an editor in the 1931 film Five Star Final (one of Robinson’s finest roles), but moviegoers knew him best at the time for his gangster portrayals in movies like Little Caesar (1931), Smart Money (1931), and The Last Gangster (1937). An attempt to escape his typecasting as a bad guy, Big Town starred the actor as “fighting managing editor” Steve Wilson of the Illustrated Press, a crusading newspaper operating in Big Town (yes, that was the name of the burg). (Eddie G. didn’t entirely shed his “bad guy” image—in some of the early Big Town broadcasts his Wilson comes across as a bit of louse.) Created, written and directed by former newspaperman Jerry McGill and sponsored by Rinso, there was no question that Big Town was a star showcase—as related in an anecdote by actor Jerry Hausner in Leonard Maltin’s The Great American Broadcast:

Big Town was created as a vehicle for actor Edward G. Robinson. Eddie G. had actually played an editor in the 1931 film Five Star Final (one of Robinson’s finest roles), but moviegoers knew him best at the time for his gangster portrayals in movies like Little Caesar (1931), Smart Money (1931), and The Last Gangster (1937). An attempt to escape his typecasting as a bad guy, Big Town starred the actor as “fighting managing editor” Steve Wilson of the Illustrated Press, a crusading newspaper operating in Big Town (yes, that was the name of the burg). (Eddie G. didn’t entirely shed his “bad guy” image—in some of the early Big Town broadcasts his Wilson comes across as a bit of louse.) Created, written and directed by former newspaperman Jerry McGill and sponsored by Rinso, there was no question that Big Town was a star showcase—as related in an anecdote by actor Jerry Hausner in Leonard Maltin’s The Great American Broadcast:

Edward G. Robinson [the show’s star] had a card table with a typewriter on it. The author of that week’s script had to sit there all day long, every day, and rewrite as we went along. He’d read a line and Eddie’d say, “I don’t like that one, cut that out, change this, change that.” He was a stickler for all these things, and that’s what made it a good show, but we had to sit there while this was being done. They rewrote and rewrote all week long, and if you were cut out, they waved you goodbye and you didn’t get any money at all. You had no protection of any kind. If your part stayed in and it was a minor supporting role, you wound up with $15, $20 for the week, $35 if you had a good part.

Big Town was a blend of no-holds-barred melodrama and socially conscious soap-boxing, as Robinson’s Wilson crusaded against society’s ills and on behalf of freedom of the press. Controversial subjects tackled on the program included examinations of racism, drunk driving, and juvenile delinquency. The show’s memorable opening intoned from an echo chamber: “The power and freedom of the press is a flaming sword! That it may be a faithful servant of all the people…use it justly…hold it high…guard it well…” Listening to surviving broadcasts today, a new generation might be puzzled by the adversarial approach of the paper’s reporters (no cozy palsy-walsy with the individuals they’re supposed to cover)—but this was a time when periodicals actively pursued investigative journalism, “comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable,” to use one of my favorite quotes.

Big Town was a blend of no-holds-barred melodrama and socially conscious soap-boxing, as Robinson’s Wilson crusaded against society’s ills and on behalf of freedom of the press. Controversial subjects tackled on the program included examinations of racism, drunk driving, and juvenile delinquency. The show’s memorable opening intoned from an echo chamber: “The power and freedom of the press is a flaming sword! That it may be a faithful servant of all the people…use it justly…hold it high…guard it well…” Listening to surviving broadcasts today, a new generation might be puzzled by the adversarial approach of the paper’s reporters (no cozy palsy-walsy with the individuals they’re supposed to cover)—but this was a time when periodicals actively pursued investigative journalism, “comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable,” to use one of my favorite quotes.

Having a big name like Eddie G.’s on any radio program would be a feather in that show’s cap…but Big Town was graced with another silver screen presence in Claire Trevor, who played Lorelei Kilbourne, the paper’s society columnist (and Steve Wilson’s love interest). Though Trevor’s performance in Dead End (1937) was just making the rounds in movie theatres shortly before Big Town’s debut, the actress wouldn’t really make it big until two years later opposite John Wayne in Stagecoach (1939). (While working on Big Town, Robinson and Trevor would star in 1938’s The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse, and later teamed up for Key Largo [1948]—the film that would win Claire a Best Supporting Actress Oscar.)

Having a big name like Eddie G.’s on any radio program would be a feather in that show’s cap…but Big Town was graced with another silver screen presence in Claire Trevor, who played Lorelei Kilbourne, the paper’s society columnist (and Steve Wilson’s love interest). Though Trevor’s performance in Dead End (1937) was just making the rounds in movie theatres shortly before Big Town’s debut, the actress wouldn’t really make it big until two years later opposite John Wayne in Stagecoach (1939). (While working on Big Town, Robinson and Trevor would star in 1938’s The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse, and later teamed up for Key Largo [1948]—the film that would win Claire a Best Supporting Actress Oscar.)

Other Big Town regulars included Ed MacDonald (as “fearless, imaginative reporter” Tommy Hughes), Gale Gordon (as District Attorney Miller), Paula Winslowe (as Wilson’s secretary Miss Foster, also played by Helen Brown), Lou Merrill, Cy Kendall and Jack Smart. As for co-star Trevor, she would exit the program in 1940 (she later complained that her role had been reduced to two lines: “I’ll wait for you in the car, Steve” and “How’d it go, Steve?”). Ona Munson took over as Lorelei…but by 1942, the program had put out a classified ad for a new Steve Wilson despite still ruling the ratings roost. A decision had been made to move the show to New York, and Edward G. Robinson decided not to follow it.

In the fall of 1943, with the series now sponsored on CBS by Sterling Drugs (Ironized Yeast, Bayer), Robinson was replaced by Broadway veteran Edward J. Pawley, with Fran Carlon as Lorelei. (Pawley would play Steve until the final months of the program in 1952, when Walter Greaza inherited the role.) New characters were introduced to the program, notably a colorful cabbie named Harry the Hack (originated by Robert Dryden, but also essayed by Mason Adams and Ross Martin), who knew the back alleys and byways of Big Town (it was a big town, you know) like the back of his hand. There was also a blind piano player named Mozart (Larry Haines) who owned a small bistro and provided underworld tips to Steve and Lorelei on the side, along with Willie the Weep (Donald MacDonald), a waterfront denizen who sobbed when he talked. Other New York acting vets included Lawson Zerbe (as the Press’ photographer, Dusty Miller), Ted de Corsia, Dwight Weist (who doubled as the show’s announcer), Bill Adams, Bobby Winckler and Michael O’Day.

In the fall of 1943, with the series now sponsored on CBS by Sterling Drugs (Ironized Yeast, Bayer), Robinson was replaced by Broadway veteran Edward J. Pawley, with Fran Carlon as Lorelei. (Pawley would play Steve until the final months of the program in 1952, when Walter Greaza inherited the role.) New characters were introduced to the program, notably a colorful cabbie named Harry the Hack (originated by Robert Dryden, but also essayed by Mason Adams and Ross Martin), who knew the back alleys and byways of Big Town (it was a big town, you know) like the back of his hand. There was also a blind piano player named Mozart (Larry Haines) who owned a small bistro and provided underworld tips to Steve and Lorelei on the side, along with Willie the Weep (Donald MacDonald), a waterfront denizen who sobbed when he talked. Other New York acting vets included Lawson Zerbe (as the Press’ photographer, Dusty Miller), Ted de Corsia, Dwight Weist (who doubled as the show’s announcer), Bill Adams, Bobby Winckler and Michael O’Day.

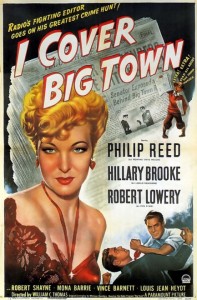

When Big Town moved to NBC in the fall of 1948, the sponsorship reverted back to Lever Brothers (though this time they pushed Lifebuoy soap instead of Rinso detergent). Its popularity was such that it inspired a short-lived B-picture franchise at Paramount beginning with Big Town (a.k.a. Guilty Assignment) in 1947, and followed by I Cover Big Town (1947), Big Town After Dark (1947), and Big Town Scandal (1948). Phillip Reed played the silver screen Steve Wilson, with Hillary Brooke portraying Lorelei. (The Big Town films were produced by William C. Thomas and William H. Pine…whose talent for low-budget filmmaking earned them the nickname “The Dollar Bills.”) Big Town later transitioned to the small screen on October 5, 1950 on CBS-TV, then moved to NBC in 1954 for two additional seasons. (The boob tube incarnation was then laid to rest in reruns, appearing under three separate titles: Byline: Steve Wilson, Headline and Heart of the City.) The radio version of the long-running series finally added its “-30-” on June 25, 1952.

When Big Town moved to NBC in the fall of 1948, the sponsorship reverted back to Lever Brothers (though this time they pushed Lifebuoy soap instead of Rinso detergent). Its popularity was such that it inspired a short-lived B-picture franchise at Paramount beginning with Big Town (a.k.a. Guilty Assignment) in 1947, and followed by I Cover Big Town (1947), Big Town After Dark (1947), and Big Town Scandal (1948). Phillip Reed played the silver screen Steve Wilson, with Hillary Brooke portraying Lorelei. (The Big Town films were produced by William C. Thomas and William H. Pine…whose talent for low-budget filmmaking earned them the nickname “The Dollar Bills.”) Big Town later transitioned to the small screen on October 5, 1950 on CBS-TV, then moved to NBC in 1954 for two additional seasons. (The boob tube incarnation was then laid to rest in reruns, appearing under three separate titles: Byline: Steve Wilson, Headline and Heart of the City.) The radio version of the long-running series finally added its “-30-” on June 25, 1952.

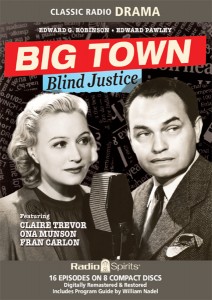

Radio Spirits’ Big Town collection Blind Justice not only features the premiere episode of the popular series, but previously uncirculated episodes and a pair of broadcasts from the Pawley-Carlon years. You can also check out the first Big Town feature film on Big Town Collection, which is supplemented with two episodes from the TV version of the show, starring Mark Stevens as Steve Wilson. In Big Town: Volume 1 and Big Town: Volume 2, it’s Patrick McVey as the “fighting managing editor,” aided and abetted by the lovely Jane Nigh as Lorelei. Grab all these collections and use them justly…hold them high…guard them well!

Radio Spirits’ Big Town collection Blind Justice not only features the premiere episode of the popular series, but previously uncirculated episodes and a pair of broadcasts from the Pawley-Carlon years. You can also check out the first Big Town feature film on Big Town Collection, which is supplemented with two episodes from the TV version of the show, starring Mark Stevens as Steve Wilson. In Big Town: Volume 1 and Big Town: Volume 2, it’s Patrick McVey as the “fighting managing editor,” aided and abetted by the lovely Jane Nigh as Lorelei. Grab all these collections and use them justly…hold them high…guard them well!