Happy Birthday, Norman Corwin!

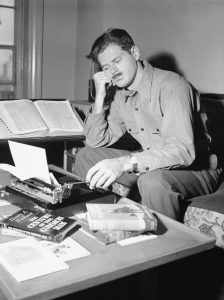

The man born Norman Lewis Corwin on this date in 1910 is universally recognized as “the poet laureate of radio.” Norman Corwin wrote and produced many of the most memorable broadcasts in the aural medium and was one of the first artists to use entertainment as a means to address the serious social issues of the day. Norman excelled at both drama and comedy, and yet his works encompassed everything from satire to fantasy to philosophy. Radio historian John Dunning noted in On the Air that “Corwin was given the treatment and almost unlimited freedom of a major star.”

Beantown (Boston) was where Norman Corwin called home, and at the age of 19 decided on a career in the fourth estate, working on The Springfield Republican as a “color man” (Corwin’s description). When the paper joined forces with WBZ in Springfield and WBZA in Boston three years later, Norman found himself on the ground floor of radio broadcasting as he provided news commentary every evening. Corwin would later relocate to Cincinnati’s WLW in 1935 for a short late-night stint as an announcer…until that station gave him a pink slip for airing reports on labor strikes (it was against station policy). Norman then returned to the Republican, where he broadcast over WBZ a program entitled Rhymes and Cadences and Norman Corwin’s Journal over WMAS (both stations were in Springfield).

Beantown (Boston) was where Norman Corwin called home, and at the age of 19 decided on a career in the fourth estate, working on The Springfield Republican as a “color man” (Corwin’s description). When the paper joined forces with WBZ in Springfield and WBZA in Boston three years later, Norman found himself on the ground floor of radio broadcasting as he provided news commentary every evening. Corwin would later relocate to Cincinnati’s WLW in 1935 for a short late-night stint as an announcer…until that station gave him a pink slip for airing reports on labor strikes (it was against station policy). Norman then returned to the Republican, where he broadcast over WBZ a program entitled Rhymes and Cadences and Norman Corwin’s Journal over WMAS (both stations were in Springfield).

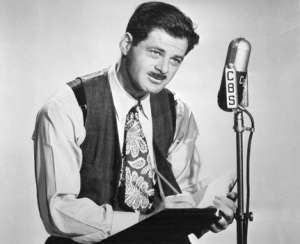

Norman Corwin continued his itineracy with a job for 20th Century Fox, churning out PR for the studio’s feature films. By 1938, he was working at New York’s WQXR on a program called Poetic License, which spotlighted many of the leading poets of the day. Corwin began his experiments with dramatization on License, which attracted the attention of W.B. Lewis, a vice president at CBS Radio. Norman was hired by the network in April of 1938 and, for most of the following decade, the Columbia Broadcasting System was his home. But Corwin worked in virtual anonymity in the beginning. His ambition was to write for The Columbia Workshop, the network’s experimental dramatic series…but Norman was convinced that he just wasn’t good enough. Yet in three short years, he would write, produce and direct Twenty-Six by Corwin—an extension of Workshop (broadcast from May 4 to November 9, 1941), which would be a precursor to his later Columbia Presents Corwin (broadcast in 1944 and 1945).

Norman Corwin continued his itineracy with a job for 20th Century Fox, churning out PR for the studio’s feature films. By 1938, he was working at New York’s WQXR on a program called Poetic License, which spotlighted many of the leading poets of the day. Corwin began his experiments with dramatization on License, which attracted the attention of W.B. Lewis, a vice president at CBS Radio. Norman was hired by the network in April of 1938 and, for most of the following decade, the Columbia Broadcasting System was his home. But Corwin worked in virtual anonymity in the beginning. His ambition was to write for The Columbia Workshop, the network’s experimental dramatic series…but Norman was convinced that he just wasn’t good enough. Yet in three short years, he would write, produce and direct Twenty-Six by Corwin—an extension of Workshop (broadcast from May 4 to November 9, 1941), which would be a precursor to his later Columbia Presents Corwin (broadcast in 1944 and 1945).

Norman Corwin’s first big success at CBS was a program entitled Words Without Music (December 4, 1938 to June 25, 1939) and the broadcast that put him on the map was “The Plot to Overthrow Christmas” (12/25/38). A delightful bit of whimsy in which demons from Hell scheme to assassinate St. Nick (House Jameson played Santa, with Will Geer as Satan). The show attracted the attention of Edward R. Murrow, who compared “Christmas” to the best of Gilbert and Sullivan. Corwin and Murrow quickly established a long friendship, with Norman demonstrating his serious side in “They Fly Through the Air with the Greatest of Ease” (02/19/39), inspired by the callousness of Benito Mussolini’s son Vittorio in describing the dropping of bombs on civilians.

Norman Corwin’s first big success at CBS was a program entitled Words Without Music (December 4, 1938 to June 25, 1939) and the broadcast that put him on the map was “The Plot to Overthrow Christmas” (12/25/38). A delightful bit of whimsy in which demons from Hell scheme to assassinate St. Nick (House Jameson played Santa, with Will Geer as Satan). The show attracted the attention of Edward R. Murrow, who compared “Christmas” to the best of Gilbert and Sullivan. Corwin and Murrow quickly established a long friendship, with Norman demonstrating his serious side in “They Fly Through the Air with the Greatest of Ease” (02/19/39), inspired by the callousness of Benito Mussolini’s son Vittorio in describing the dropping of bombs on civilians.

When Words Without Music finished its run, Norman Corwin moved on to the short-lived So This is Radio , followed by The Pursuit of Happiness. The aforementioned Twenty-Six by Corwin was next, which included classics such as “The Log of the R-77″ [05/11/41] and “The Odyssey of Runyon Jones” [06/08/41]. It was that series that prompted playwright Archibald MacLeish to suggest Norman to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who wanted radio to help celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Bill of Rights. Norman’s contribution, “We Hold These Truths” (12/15/41; broadcast on all four networks), had a special resonance when it aired just a week after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Actor James Stewart (portraying an average American citizen who acted as a “sounding board” for the broadcast’s patriotic sentiments) was just one of many participants in the all-star cast of this critically acclaimed production.

When Words Without Music finished its run, Norman Corwin moved on to the short-lived So This is Radio , followed by The Pursuit of Happiness. The aforementioned Twenty-Six by Corwin was next, which included classics such as “The Log of the R-77″ [05/11/41] and “The Odyssey of Runyon Jones” [06/08/41]. It was that series that prompted playwright Archibald MacLeish to suggest Norman to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who wanted radio to help celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Bill of Rights. Norman’s contribution, “We Hold These Truths” (12/15/41; broadcast on all four networks), had a special resonance when it aired just a week after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Actor James Stewart (portraying an average American citizen who acted as a “sounding board” for the broadcast’s patriotic sentiments) was just one of many participants in the all-star cast of this critically acclaimed production.

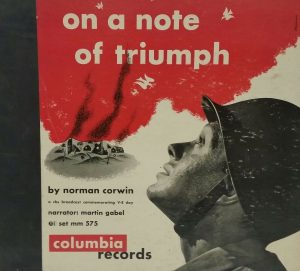

Norman Corwin followed “Truths” with several series: This is War!, An American in England (a collaboration between Corwin and Murrow), Passport for Adams, and An American in Russia. Columbia Presents Corwin premiered on March 7, 1944 and spotlighted such presentations as “The Long Name None Could Spell” (03/14/44; on Czechoslovakia) and “The Lonesome Train” (03/21/44; about the train journey of Abraham Lincoln’s corpse). In between this first series of Columbia Presents Corwin and the second, Norman became notorious for a November 6, 1944 broadcast on behalf of the Democratic National Committee to re-elect FDR (many big-name celebrities, like Judy Garland and Humphrey Bogart, participated in what members of the loyal opposition [the GOP} justifiably called “propaganda”). “On a Note of Triumph”—broadcast on May 8, 1945—commemorated V-E Day with an awe-inspiring presentation that many consider Corwin’s “crowning touch.”

Norman Corwin followed “Truths” with several series: This is War!, An American in England (a collaboration between Corwin and Murrow), Passport for Adams, and An American in Russia. Columbia Presents Corwin premiered on March 7, 1944 and spotlighted such presentations as “The Long Name None Could Spell” (03/14/44; on Czechoslovakia) and “The Lonesome Train” (03/21/44; about the train journey of Abraham Lincoln’s corpse). In between this first series of Columbia Presents Corwin and the second, Norman became notorious for a November 6, 1944 broadcast on behalf of the Democratic National Committee to re-elect FDR (many big-name celebrities, like Judy Garland and Humphrey Bogart, participated in what members of the loyal opposition [the GOP} justifiably called “propaganda”). “On a Note of Triumph”—broadcast on May 8, 1945—commemorated V-E Day with an awe-inspiring presentation that many consider Corwin’s “crowning touch.”

Norman Corwin’s second series of Columbia Presents Corwin featured some of his most fondly remembered work including “The Undecided Molecule” (06/17/45) and “Fourteen August” (08/14/45). Although Norman was given unprecedented freedom at his time with CBS, after WW2 the writing was on the wall. Corwin would later recall that one of his fervent champions, CBS president William S. Paley, suggested to him during a train trip that the author’s future scripts be fashioned for a more commercial audience. After the success of One World Flight in 1947, the network attempted to usurp half of the money Norman received for his subsidiary rights during contract negotiations, Corwin left CBS and joined United Nations Radio in 1948 (and continued his fine work with such presentations as “Document A/777” and “Could Be”).

Norman Corwin’s second series of Columbia Presents Corwin featured some of his most fondly remembered work including “The Undecided Molecule” (06/17/45) and “Fourteen August” (08/14/45). Although Norman was given unprecedented freedom at his time with CBS, after WW2 the writing was on the wall. Corwin would later recall that one of his fervent champions, CBS president William S. Paley, suggested to him during a train trip that the author’s future scripts be fashioned for a more commercial audience. After the success of One World Flight in 1947, the network attempted to usurp half of the money Norman received for his subsidiary rights during contract negotiations, Corwin left CBS and joined United Nations Radio in 1948 (and continued his fine work with such presentations as “Document A/777” and “Could Be”).

Norman Corwin had a little success with adapting his radio output to motion pictures: his classic Columbia Workshop production of a talking caterpillar (“My Client Curley,” adapted from Lucille Fletcher’s story) became a Cary Grant film in 1944 called Once Upon a Time. The author would later pen screenplays for films like The Blue Veil (1951), Scandal at Scourie (1953), No Place to Hide (1955), and Lust for Life (1956; which earned him an Oscar nomination). But Norman would never lose his love for radio; he would contribute to later revival attempts like The Sears Radio Theatre and was the focus of several National Public Radio series in the 1980s/1990s including Thirteen by Corwin and More by Corwin. The man who would be rewarded with tributes in the form of Peabody, Emmy and Golden Globe Awards reached the centennial birthday mark in 2010…but would leave this world for a better one on October 18, 2011.

Norman Corwin had a little success with adapting his radio output to motion pictures: his classic Columbia Workshop production of a talking caterpillar (“My Client Curley,” adapted from Lucille Fletcher’s story) became a Cary Grant film in 1944 called Once Upon a Time. The author would later pen screenplays for films like The Blue Veil (1951), Scandal at Scourie (1953), No Place to Hide (1955), and Lust for Life (1956; which earned him an Oscar nomination). But Norman would never lose his love for radio; he would contribute to later revival attempts like The Sears Radio Theatre and was the focus of several National Public Radio series in the 1980s/1990s including Thirteen by Corwin and More by Corwin. The man who would be rewarded with tributes in the form of Peabody, Emmy and Golden Globe Awards reached the centennial birthday mark in 2010…but would leave this world for a better one on October 18, 2011.

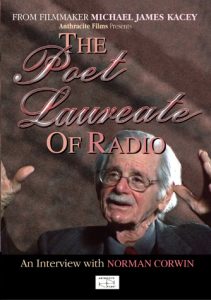

The first volume in Jason Hill’s Life in the Past Lane series (which compiles interviews with personalities who had a hand in creating twentieth century entertainment) features a chapter with today’s birthday boy (and his biographer, R. Leroy Bannerman) and is available for purchase at Radio Spirits. But you’re also going to want to slip The Poet Laureate of Radio into your shopping cart—it’s a 2006 documentary directed by Michael James Kacey, and it’s an extended interview with Norman Corwin as he dissects a variety of topics and subjects (everything from fascism to William Shatner) as only the master can. Happiest of birthdays to Norman Corwin!

The first volume in Jason Hill’s Life in the Past Lane series (which compiles interviews with personalities who had a hand in creating twentieth century entertainment) features a chapter with today’s birthday boy (and his biographer, R. Leroy Bannerman) and is available for purchase at Radio Spirits. But you’re also going to want to slip The Poet Laureate of Radio into your shopping cart—it’s a 2006 documentary directed by Michael James Kacey, and it’s an extended interview with Norman Corwin as he dissects a variety of topics and subjects (everything from fascism to William Shatner) as only the master can. Happiest of birthdays to Norman Corwin!