Happy Birthday, Irving Brecher!

The only scriptwriter to receive sole credit on two of the Marx Brothers’ classic feature film comedies was Irving Brecher, born in the Bronx on this date in 1914. An impressive achievement, to be sure…though it should be noted that those two romps—At the Circus (1939) and Go West (1940)—rank toward the bottom of the Brothers’ oeuvre where dedicated Marxists are concerned. That nitpicky criticism aside, Groucho Marx (as well as collaborator S.J. Perelman) thought most highly of Irving, once remarking that Brecher possessed a quick, spontaneous wit that was the equal of George S. Kaufman and Oscar Levant. It was while trying to create a radio program for Groucho that Irving would inadvertently bring to life one of the medium’s best-remembered and beloved sitcoms.

Even as a teenager, Irving Brecher was somehow destined to become one of the respected elders of comedy. He was writing humor for his high school newspaper in Yonkers, while at the same time earning $6 a week as a reporter for The Yonkers Herald. While toiling as an usher and errand boy in a Manhattan movie theatre, Irving supplemented his income by supplying jokes to columnists like Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan. When a reporter from Variety informed him that comedian Bob Hope was laying audiences in the aisles with some of his material, Brecher quickly learned that he could make a living at writing comedy. He persuaded that same reporter to print an ad in Variety touting Brecher’s services with the observation: “Positively Berle-proof gags—so bad not even Milton will steal them.”

Even as a teenager, Irving Brecher was somehow destined to become one of the respected elders of comedy. He was writing humor for his high school newspaper in Yonkers, while at the same time earning $6 a week as a reporter for The Yonkers Herald. While toiling as an usher and errand boy in a Manhattan movie theatre, Irving supplemented his income by supplying jokes to columnists like Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan. When a reporter from Variety informed him that comedian Bob Hope was laying audiences in the aisles with some of his material, Brecher quickly learned that he could make a living at writing comedy. He persuaded that same reporter to print an ad in Variety touting Brecher’s services with the observation: “Positively Berle-proof gags—so bad not even Milton will steal them.”

Irving’s brashness caught the comedian’s eye (Milton was certainly no slouch in the insolence department himself), and from that moment on Brecher was an employee of Berle Enterprises, supplying gags for Milton’s vaudeville act and scripting his first forays into radio. (Irving also wrote—along with his later collaborator Alan Lipscott—a radio program for the comedy team of Willie and Eugene Howard.) Milton Berle’s first major network program was CBS’ The Gillette Original Community Sing, a 45-minute broadcast on which Brecher was the sole writer. (Even with the music on the program, Irving was having to write twenty-five minutes of comedy every week.) Berle would later remark that Irving was the only man he knew “who wrote a radio program every week all by himself.”

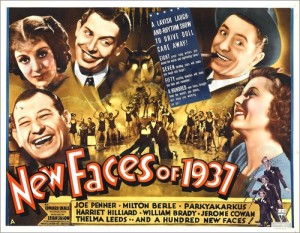

Milton Berle would be Irving Brecher’s ticket to a career in movie screenwriting. While churning out the Gillette program, Irving was pressed into assisting on the screenplay for New Faces of 1937, which not only featured his radio boss but other on-the-air favorites such as Joe Penner, Harry “Parkyakarkus” Einstein, Harriet Hilliard Nelson, Bert “The Mad Russian” Gordon, and Patricia “Honey Chile” Wilder. Brecher also contributed additional dialogue to Fools for Scandal (1938), a film co-directed by Mervyn LeRoy. LeRoy was a fan of Irving’s work on Berle’s radio program, and hired him to punch up the material of Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, and Bert Lahr on The Wizard of Oz (1939). This kicked off a long association with MGM; in addition to the screenplays for At the Circus and Go West, Brecher was responsible for Shadow of the Thin Man (1941), Du Barry Was a Lady (1943), Best Foot Forward (1943), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944—which earned Irving an Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay), and Yolanda and the Thief (1945).

Milton Berle would be Irving Brecher’s ticket to a career in movie screenwriting. While churning out the Gillette program, Irving was pressed into assisting on the screenplay for New Faces of 1937, which not only featured his radio boss but other on-the-air favorites such as Joe Penner, Harry “Parkyakarkus” Einstein, Harriet Hilliard Nelson, Bert “The Mad Russian” Gordon, and Patricia “Honey Chile” Wilder. Brecher also contributed additional dialogue to Fools for Scandal (1938), a film co-directed by Mervyn LeRoy. LeRoy was a fan of Irving’s work on Berle’s radio program, and hired him to punch up the material of Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, and Bert Lahr on The Wizard of Oz (1939). This kicked off a long association with MGM; in addition to the screenplays for At the Circus and Go West, Brecher was responsible for Shadow of the Thin Man (1941), Du Barry Was a Lady (1943), Best Foot Forward (1943), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944—which earned Irving an Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay), and Yolanda and the Thief (1945).

As an MGM employee, Brecher was contracted to work solely for the studio—this allowed him to keep his hand in radio by contributing comedian Frank Morgan’s material for MGM’s Good News radio program. Any other radio work had to be done on the Q.T., so Irving did not receive credit for the brief time he worked on Al Jolson’s show for Old Gold cigarettes. Brecher also dusted off a pilot he had written, The Flotsam Family, for his good friend Groucho to jumpstart Marx’s sagging radio career. An audition record was produced, and while Groucho was undeniably funny, the concept of the series—the anarchic Groucho as the patriarch of a family—just didn’t click with either the audience or potential sponsors. Then Irving happened to spot actor William Bendix in the film The McGuerins from Brooklyn (1942). Brecher was convinced that with Bendix in the lead role, The Flotsam Family could be a hit—and this prophecy came to pass when the new series, retitled The Life of Riley, premiered over the Blue Network for The American Meat Institute on January 16, 1944.

As an MGM employee, Brecher was contracted to work solely for the studio—this allowed him to keep his hand in radio by contributing comedian Frank Morgan’s material for MGM’s Good News radio program. Any other radio work had to be done on the Q.T., so Irving did not receive credit for the brief time he worked on Al Jolson’s show for Old Gold cigarettes. Brecher also dusted off a pilot he had written, The Flotsam Family, for his good friend Groucho to jumpstart Marx’s sagging radio career. An audition record was produced, and while Groucho was undeniably funny, the concept of the series—the anarchic Groucho as the patriarch of a family—just didn’t click with either the audience or potential sponsors. Then Irving happened to spot actor William Bendix in the film The McGuerins from Brooklyn (1942). Brecher was convinced that with Bendix in the lead role, The Flotsam Family could be a hit—and this prophecy came to pass when the new series, retitled The Life of Riley, premiered over the Blue Network for The American Meat Institute on January 16, 1944.

The Life of Riley became a huge success on radio, and it also paved the way for Irving Brecher’s brief directing career in movies. A big screen version of the series was released by Universal in 1949 (which Brecher also produced and wrote), allowing Irving to also sit in the director’s chair on Somebody Loves Me (1952) and Sail a Crooked Ship (1961). The success of the movie led to a TV version of the radio hit, but because star William Bendix was under contract to producer Hal Roach—and Roach vetoed Bill’s participation on the small screen, believing it to be just “a fad”—Brecher, who was producing the small screen version, had to go with an actor he was originally warned away from: Jackie Gleason. The TV Life of Riley would only last one season (the show’s sponsor, Pabst, essentially wanted the time slot to schedule prizefights) despite winning an Emmy Award. A later incarnation of the show enjoyed a bit more longevity, airing on NBC-TV from 1953 to 1958.

The Life of Riley became a huge success on radio, and it also paved the way for Irving Brecher’s brief directing career in movies. A big screen version of the series was released by Universal in 1949 (which Brecher also produced and wrote), allowing Irving to also sit in the director’s chair on Somebody Loves Me (1952) and Sail a Crooked Ship (1961). The success of the movie led to a TV version of the radio hit, but because star William Bendix was under contract to producer Hal Roach—and Roach vetoed Bill’s participation on the small screen, believing it to be just “a fad”—Brecher, who was producing the small screen version, had to go with an actor he was originally warned away from: Jackie Gleason. The TV Life of Riley would only last one season (the show’s sponsor, Pabst, essentially wanted the time slot to schedule prizefights) despite winning an Emmy Award. A later incarnation of the show enjoyed a bit more longevity, airing on NBC-TV from 1953 to 1958.

The 1953-58 Life of Riley was produced without the participation of its creator (instead, Irving leased NBC the rights to the show) …but at that time, Irving Brecher was busy with another TV sitcom: The People’s Choice. This series starred Jackie Cooper as a city councilman who was secretly married to the mayor’s daughter (played by Patricia Breslin). Folks familiar with the show no doubt remember it for Cooper’s pet basset hound (Cleo), who frequently commented on the action with the voice of radio actress Mary Jane Croft. Other Brecher projects included an episode of The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, a TV adaptation of Meet Me in St. Louis, and the screenplays for the films Cry for Happy (1961) and Bye Bye Birdie (1963). Birdie would be the funnyman’s show business swan song; Irving enjoyed a relaxing retirement as an elder statesman of comedy. After his death in 2008, his remarkable life and career was the subject of a posthumously-released memoir, The Wicked Wit of the West.

The 1953-58 Life of Riley was produced without the participation of its creator (instead, Irving leased NBC the rights to the show) …but at that time, Irving Brecher was busy with another TV sitcom: The People’s Choice. This series starred Jackie Cooper as a city councilman who was secretly married to the mayor’s daughter (played by Patricia Breslin). Folks familiar with the show no doubt remember it for Cooper’s pet basset hound (Cleo), who frequently commented on the action with the voice of radio actress Mary Jane Croft. Other Brecher projects included an episode of The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, a TV adaptation of Meet Me in St. Louis, and the screenplays for the films Cry for Happy (1961) and Bye Bye Birdie (1963). Birdie would be the funnyman’s show business swan song; Irving enjoyed a relaxing retirement as an elder statesman of comedy. After his death in 2008, his remarkable life and career was the subject of a posthumously-released memoir, The Wicked Wit of the West.

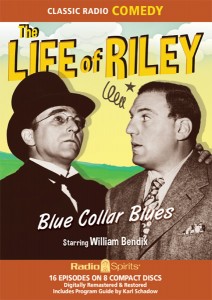

Milton Berle once remarked of his former employee: “As a writer, Irving Brecher really has no equals. Superiors, yes.” (It’s possible that Brecher even wrote that gag himself.) At Radio Spirits, we’re all too aware of the impact that today’s birthday boy made in radio comedy: we have two collections of his finest achievement, The Life of Riley, available in Magnificent Mug and Blue Collar Blues. That memoir mentioned previously, The Wicked Wit of the West, is also available for purchase; written in collaboration with Hank Rosenfeld, it’s choc-a-bloc with great anecdotes on Irving’s incredible show business career (including a fishing trip with Groucho and how Brecher paid for Jackie Gleason’s teeth). Happy birthday to Irving Brecher, the man who continues to show old-time radio fans just how revoltin’ a development can be.

Milton Berle once remarked of his former employee: “As a writer, Irving Brecher really has no equals. Superiors, yes.” (It’s possible that Brecher even wrote that gag himself.) At Radio Spirits, we’re all too aware of the impact that today’s birthday boy made in radio comedy: we have two collections of his finest achievement, The Life of Riley, available in Magnificent Mug and Blue Collar Blues. That memoir mentioned previously, The Wicked Wit of the West, is also available for purchase; written in collaboration with Hank Rosenfeld, it’s choc-a-bloc with great anecdotes on Irving’s incredible show business career (including a fishing trip with Groucho and how Brecher paid for Jackie Gleason’s teeth). Happy birthday to Irving Brecher, the man who continues to show old-time radio fans just how revoltin’ a development can be.